Written in December 1997 by a 16 year old white girl. It is a good response to Ruby Payne's book on Understanding Poverty, because it is actually written by a poor person:

I was born to a poverty-stricken, large family in a small town in Iowa called Denver. I was the fifth of six, and although my mother was already thirty-five, she insisted on giving birth to me at home, in the tiny apartment in which we lived, rather than at a hospital. My parents had been paranoid of the government, and felt that it had too much control over people's decisions. They planned to keep my birth, and entire existence, a secret. My brothers and sister were told to keep quiet about it all. It worked for quite a long time, but things eventually had to change. It must have been hard times then. I'm not sure why, but a few months later, my mother and father both lost their jobs, and the lease on the apartment would soon be up.

The only income was the bi-weekly paycheck of my nine-year-old sister Deborah's paper-route. My grandfather owned a small house in the outskirts of the tiny town. He offered it to my parents, without rental expenses. They eagerly accepted, moving out just days before actually being evicted anyway. I was eight months old, and it was November. With winter coming and no heating in the house, my still-unemployed parents sought the help of the government. When the county checked into my information, they discovered, oddly enough, that I was never registered; didn't exist. Without proper papers, life could be difficult. The county insisted that I be registered, and so it happened... nine months after I was born. After finally having the birth certificate, we all moved into the temporary foster families a few dayslater.

My parents did the best they could. My father found a job as a janitor, and my mother as a substitute teacher. After six months, with a little money saved up, they began the process of getting us back from foster care. The county, however, refused. They demanded a few more months, and my parents, though devastated, got a lawyer (paid for by the county itself), and eventually got us back, one year after the initial decision. I was over a year old when we returned. Deb was about eleven,Dave nine, Daniel six, and John was three. My mother noticed something odd. John had a bunch of bruises all over his body, and she kneeled down on her knees and asked him if he had been hit. Yes, he replied with broken baby-talk, and not only that, but I had been, too. Our foster parents had beaten us, and our ages added together barely summed five. But she noticed much more than just that. All of her children seemed to have changed. On the surface they had grown a little, their hair had gotten a few inches longer, their clothes a little bitsmaller. But it was the personalities themselves that had been altered. Deb was now a perfectionist, doing everything for the family.

David had spent his foster-care time emotionally abused by his foster parents. He was often "set up" by the natural son, and blamed for any problem or fight with the son. Daniel had spent his foster-care time hiding under tables and crying for his mother. His only impression was that his big brother was being treated as the whipping boy, who had done nothing todeserve it. Dave started stealing the little money Mom had, and sneaking out to play at endless days and nights at the arcades. He always brought Daniel along. It seemed like harmless boys' play at first, but it later got a lot worse. The one who had changed the most, however, was the one who was at the most tender age--me. My mother was devastated at the changed baby before her. When before, I would happily hug her and smile, eat and sleep peacefully, the baby now yelled at the top of her lungs, atenothing, and spent long nights screaming until she fell asleep. There were no more lullabies now, I refused to hear. There were no hugs now, I wouldn't be handled. Being with her once happy baby was now a chore for my worn-out mother. John, too, was changing. With Mom spending all of her time focused on me, he spent his toddlerhood as a sad little boy, left somewhere in the darkness of our gray lives. We eventually moved to a rented house in Waterloo, Iowa, a city with a quite a few people.

Mother grew to accept her changed children. She could do nothing, no matter how she tried. When I was three, she gave birth to her sixth and last child, Joseph. Joe brought me a little peace and happiness. I pushed him in the stroller, sang, cuddled him and kissed him. He was my dolly, my real dolly, and I loved him more than any other creature in the world. I spent endless hours with him, taking walks. I would push his stroller to some far-off land at the end of the block... It was at night, though, that we were forbidden to be outdoors. Our neighborhood was dangerous,and I took care to always be by him. But I could not protect him from everything, because when I was four and he a year, my parents separated. My father moved to the damp basement of a dirty, old apartment. Strange enough, though, my mother never spoke a bad word against him. They had grown apart. His self-esteem tested low on a hospital test he had taken. He scored four points out of one hundred, and he felt unworthy as a father. Mother wasn't much better, and their struggle together ended ashe packed his last suitcase into his friend's car. Through the half-torn screen door, I waved good-bye, and took Joe's hand and waved it, too. I didn't see him wave back, though. The car just drove away after he slammed the car door shut. Mom's depression got worse and worse. She laid in bed for most of the day, and once again, it was Deb's responsibility to see that all got done. Deb never missed a day of school, and when she turned fifteen, she applied for a part-time job as a waitress. Every paycheck went back to the family.

The child-support check was barely a dent in what we needed. Mom was given a check every month for fifty dollars for six children. She just accepted it with all of the other sadness around her. She gotwelfare, too, but that wasn't very much, either. Mother had grown up the daughter of a wealthy chiropractor who created special chairs and campers in his free time. She had always been well taken care of, as a child. The life she saw now pulled her still further into depression. We moved once again, to a better neighborhood, on the other side of town. The house had two stories (and a basement), and it was the ultimate playhouse for my siblings and me. When I was in kindergarten, we moved again, to a house on the other side of town. At this point, we had lived in three different ends of the city. I changed schools this time, and went to school with John. Toward the end of that year, mymother attempted suicide, and almost succeeded. John's second-grade teacher took us to her house. I'm not quite sure just how long we stayed with Ms. Navarro, but at some point, she took us to Chicago to visit her relatives. I found comfort there, in Chicago.

We stayed in a huge apartment building that was at least thirty stories high. We played on the elevator until the Mexican bellboy yelled at us to ride the elevator properly, or simply go to our apartment. We would then go outside anddash across the road to the playground across the street. We swung for hours, on the rusty, red swing set somewhere in the middle of the Windy City. Although my brother and I were the only white kids there, we were warmly accepted by the young black community. We spent the whole time outside, digging in the dirt and eating dusty Cheetos off the sand. Although we had all once been well-behaved, decent kids, David and Daniel were worse now, going rarely to school and always getting calls from the school. They were setting the pattern for John to one day follow. That summer, my sister left to go to 'Upward Bound', a program for poor kids, designed to make them aware that hope existed, that finishing college was a good way to escape the poverty. That voice inDeb's ear whispered 'Get out! Get out!' She went that summer, and in the meantime, we were waking up early to walk down to school for the free breakfast.

Within out city's poor community, all the schools gave free meals out in the summer to children under eighteen. Throughout the next few years (and even when we still lived in the bad neighborhood) I, myself, sank into a deep depression. I think I was about seven when I met Ruth, a friend of my mom's. They had met each other in the mental hospital and had a lot of the same problems. Ruth had once been married and had had a son named Tony. But after the divorce, Tony was taken from her, and she was left alone. She liked me,though, and always took me to her apartment (ironically) in the same town in which I was born. We went horseback riding, drew pictures, talked about our favorite subject--kittens. For her, I was like the daughter she never had. To me, though, she was my best friend.

Nobody had ever listened to me the way she had. She assured me that whatever I wanted to be -an artist- I would surely have success. She said I hadwhat it took to overcome anything. I loved her a lot. When I was eight, my mother drove me to Ruth's town. I hadn't seen her in a while, but the direction we were heading didn't seem to be right. We were driving to a funeral parlor, I later discovered, because Ruth had hung herself a few days earlier. I just blinked a lot and wanted her to wake up. I didn't realize she was dead. When I was eleven, my sister graduated college. She had succeeded and had been accepted to graduate school at the University of Michigan, five hundred miles away, to study social work and psychology. Her choice of career study probably stemmed from her own life's strange roots; it might seem logical. Dave spent most of his days with his friends. He had a love for alcohol and drugs. I think it stemmed from his foster care time. One time, I wondered about his experience there because Mom had often told me that Dave had really been changed, so I asked him. The big, six-foot-five man nicknamed 'Ogre' (also tattooed on his left shoulder), began to cry.

I saw tears forming in his eyes, and he quietly said 'I don't want to talk about it'. I accepted it, knowing that it must have really been bad. I understood him, a little, and it couldn't help to make me sad. In anycase, I never brought it up again. It was within my thirteenth year that I learned a lot. At Christmas time, my sister came home. She asked what had happened, and I just shrugged. Questioning my mother, Deb asked me then, if I would like to come live with her in Michigan. She had an apartment, she said, and although it was only one bedroom, we could take turns sleeping on the couch, and it would all be better. I smiled, and accepted. After theholidays, we were sitting in her apartment in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and I was registered for the second half of my eighth grade year at the local middle school. Adjusting was hard in the eighth grade year. The apartments where my sister lived were filled with people from all over the world. I rode the bus to a new school with many strange languages swirling around in the bus. The school I had attended in Iowa had molded me into who I was. I had been taught to be scared, actually, and the schools weren't very safe. With fights every day, weapons and horrible stories of what happened to stuck-up girls, I saved myself by just never talking, except to my friends. I never brushed my hair in class--that was too preppy. I never put make-up on in school--that was slutty. Giving anybody a hug would have been seen as a casual, relaxed gesture, and that sort of thing might attract a bully to take those good feelings away. I was just preventing what could eventually get me into trouble.

In Ann Arbor, however, everything was so much more peaceful. The students would walkdown the hallway and give each other hugs! They would brush their hair in class, and actually respected the teachers. Although it was wonderful, it was still hard for me to accept. It was just too strange. I only had a few friends, and I spent time with them just in the school. With my sister always at work or at school, I spent all of my free time writing long letters back home to Iowa. Thinking back, though, I don't think that I had too much homesickness. We visited home all of the time. But slowly, my sense of security was returning. Nothing was stolen from me, and I actually felt safer to voice my opinion in school. I stayed out in Michigan with Deb for my ninth grade year, and went again to Upward Bound afterwards. My tenth grade year, is when I decided I needed to do more activities in order to get into good colleges. My grades were nice enough, but I hadn't participated in a single sport. I applied to 'Wendy's'. I worked practically every day, and gave up my weekends, too, to work long hard hours. On top of that, Iwas participating in a group which met every Wednesday called S.E.E.D. (Students Educating Each other about Discrimination). Things happened.

Sometime in October, we got a call in the middle of the night that David had killed himself. He had been high when he did it, and he got into his 72' Ford and used a vacuum tube to force the exhaust back into the car. He was found, about five minutes too late, by Daniel. Going to the funeral, I just thought about how we had been such rivals, always fighting and quarreling. But we were also very close at the same time. He was twenty-three when he died--too young. I blame his sadchildhood for the depression that no pill could have soothed. He will always remain with me, and I must always be careful of what I see, I may start to cry... I have written this whole session of my life (although I can't remember everything and some things I just chose to leave out) because I am changing here. I am growing into an adult woman, looking back at where I've come from, and where I'm going. I don't know if anything good will come out of this year, but hopefully, I will look back at this not-so-good upbringing of mine and try to make sense out of it. I don'tknow what keeps me alive, actually. Maybe Dave was the sane one! Maybe what keeps me hanging on is my own insanity... Who knows, maybe I'll one day know.

Sunday, June 10, 2007

Poverty from Up Close and Personal

Posted by

DMF

at

10:48 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: anthropology, literature, personal experience, poverty

Friday, June 08, 2007

Dems plan 4.3% surcharge tax on richest households...

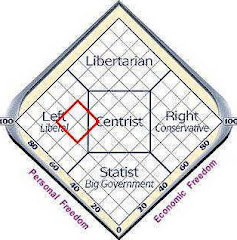

House Democrats looking to spare millions of middle-class families from the expensive bite of the alternative minimum tax are considering adding a surcharge of 4 percent or more to the tax bills of the nation's wealthiest households.

read more digg story

Where your tax dollars sometimes go...

http://www.dmegivern-dfoster.net/Des_Moines_Register_article.pdf

Consequences of lack of health insurance...a typical white American male who develops first schizophrenia and then diabetes: Warning gory pictures.

http://www.dmegivern-dfoster.net/Consequences.html

Posted by

DMF

at

9:27 PM

0

comments

![]()

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)