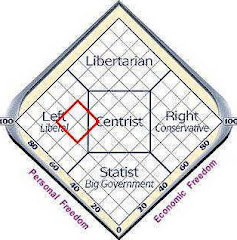

Our first Christmas vacation morning was ruined by this alleged business. As it turns out, this dealership is not about Toyota, it is a center for right-wing propoganda.

Our first Christmas vacation morning was ruined by this alleged business. As it turns out, this dealership is not about Toyota, it is a center for right-wing propoganda.

This is a website paying homage to wisdom. Education and experience combined with the power of critical thinking have served me well, and I hope others will be encouraged to consider their own life's learning.

Our first Christmas vacation morning was ruined by this alleged business. As it turns out, this dealership is not about Toyota, it is a center for right-wing propoganda.

Our first Christmas vacation morning was ruined by this alleged business. As it turns out, this dealership is not about Toyota, it is a center for right-wing propoganda.

Posted by

DMF

at

1:42 PM

10

comments

![]()

Understanding and Experiencing White Privilege:

Even after nearly 8 years in a graduate social-work program—in an environment in which discussion of oppression and privilege occurred frequently—I still had trouble with the idea that I had personally benefited from many advantages. It was not that I cognitively denied my privileges, particularly those gleaned from being White; my challenge was the intersection of being White and growing up poor. I struggled with feeling privileged when I could not get over feeling deprived; I could make a direct connection between current miseries and lifelong disadvantages. Educating others around me who just "didn't get economic or class oppression" drew my focus away from my own white privilege.

Roots of an Identity

Although I am a white, heterosexual woman, the identity most salient throughout my life was "poor trash"—a welfare child. Many life experiences reinforce the importance of this identity over the more privileged identities I enjoy. Both of my parents suffered from psychiatric illnesses. My mother received disability payments, and my father was employed as a janitor which meant minimal income. Economic struggles within my family led to bouts with homelessness, daily reliance on the Salvation Army for meals, and dependence on charity from public and private sources. Lack of food and heat led child-protective services to remove my siblings and me from my parents to be placed in foster care. When we were eventually returned to our parents the strain of family separation and poverty led my parents to divorce shortly thereafter. My mother became a single parent to six children, while my father moved into a roach-infested single room occupancy hotel.

The neighborhood in which we were being raised was dangerous and dilapidated. Indeed, the rampant negative influences likely contributed significantly to the fact that three of my younger siblings were mandated to services within the juvenile justice system, and two of them became drug dependent. Eventually, one of my brothers committed suicide. I will always be convinced that poverty and our childhood life circumstances played the largest role in his death.

My departure from this life of poverty at the age of 17 was the result of support from family and friends, an extensive series of governmental interventions (ranging from Head Start to Project Upward Bound), and a natural inclination toward academia. As I was driven off to college, I felt relieved to have escaped that life of dispossession. But unfortunately the feeling was short-lived, for it was during college and graduate school that I discovered the seemingly permanent effects of my economic history. The majority of my classmates came from middle-class to upper-middle-class families. There were daily reminders of our differences.

In political science and economics classes, my privileged college classmates degraded welfare recipients. I was too frightened of social exclusion to speak up. Instead, I silently sat in isolation, absorbing the significant social distance between us. Outside of class, many acquaintances were frustrated with my seeming "unwillingness" to spend more time with them in social activities and less time at work. They did not understand that for me, work was not a choice.

My full-time work schedule throughout college did not allow much time for socializing. Whether I was serving other students food at the school's cafeteria during the day or taking their orders at the popular local restaurant in the evening, I would overhear college classmates complaining about reductions in their allowances from $500 a month to $250. They did not have to pay their college expenses, and they even got an allowance. They did not need to work. I fantasized about what that would be like. It was hard not to feel bitter as my own class work often got behind in a heavy work week. Chronic fatigue also made me prone to headaches, stomach pain, and colds.

As it turned out, being poor had shaped my identity, had somewhat become my identity, and continued to play itself out. During graduate school, I found myself in the role of parent when I obtained custody of my two youngest siblings, accumulating over $125, 000 in student loan debt while attempting to raise them on a graduate student's stipend and other meager employment. It was under these circumstances of economic hardship that I studied oppression and privilege in my graduate classes and learned extensively about white privilege. Certainly, it felt to me as though my entire life had been defined by deprivation. If there were white privileges to be recognized, I could not see them. In my mind, what on earth good had it done to be white? It had not spared me hunger, frostbite, lice, poor medical care, ridicule, violence, or trauma. This feeling of deprivation was especially true here because other graduate students, including students of color, who had spent their lives in material comfort, were by far the majority in graduate school.

The Embers of Transformation

Eventually, I gained an intellectual, if not intuitive, understanding of privilege through my graduate program. Vowing to continue work on my own issues of privilege, I decided to become a co-facilitator with a well-regarded lead instructor, Dr. Michael Spencer . Dr. Spencer offers multicultural dialogue groups as a major means for learning about social justice, oppression, and privilege in his Contemporary Cultures in the United States class. I maintained the goal of focusing on my privileged identities, but I often felt ambivalent. On the one hand, I felt bitterness, guilt, and defensiveness at being blamed for my culpability in race oppression as class members of color described their experiences. On the other hand, I felt envy and bitterness toward those individuals who had been economically privileged throughout their lives. I craved their basic privilege of getting fundamental needs met and the sense of security that elicited.

About mid-semester, I was asked by Dr. Spencer to give a presentation on classism and poverty. He knew this was an area I knew a lot about. As I presented general information to the class, I shared specific details from my personal experiences to give fellow students a sense of how economic labeling and stigmatization make an impact. At one point, I showed the class a Child Protective Services document that declared me guilty of child neglect when I left two of my siblings in the house while I went to rescue another younger sibling being beaten by kids at the local park. I was 12 years old at the time. We discussed whether the guilty verdict would have occurred for a middle-class family under the same circumstances, and most class members agreed that it likely would not have.

The presentation stirred a mix of emotions in me. To share the lack of power, the deprivation, and the humiliation was empowering. Nonetheless, the stigma of poverty and child neglect, even though I was only 12 years old at the time, still stung. I felt I had performed a duty to other poor people by telling our story, but the cost was shame that took weeks to shake off.

At the end of the presentation, an African-American graduate student I respected a great deal approached me. She told me honestly, "I feel bad for you; but to be blunt, by the end of your talk, I was still thinking, 'So what? You're still White.' I guess I think that being White makes a big difference." Her words stung; her expression seemed defiant and accusatory. It felt as though my oppression was deniable, because I was white. The weight of race oppression was her burden. To me, it felt as if she could not see my burden of class oppression or her own class privilege as long as her awareness stayed entirely within race oppression.

It dawned on me, eventually, that I was not going to be able to own my white privilege until I let go of enough of my own oppression to really listen and internalize the privilege. My classmate's comment was a precipitant to the gradual coherence and redirection of my conflicting thoughts and feelings. There we had been, both in pain from dealing with the ramifications of oppression, yet we had been at odds.

When I recollected that exchange later on, the importance of accepting my white privilege became clear to me on an emotional level because, if I was unwilling to move beyond my oppression, how could I expect anyone else to do as much? This meant I was going to have to really attend to all of the daily instances in which my race advantaged me. If I applied for an apartment, I knew any rejection would be because I didn't have enough credit. I did not have to question whether my race was a factor. I had personally witnessed millions of examples of white privilege as I grew up in a predominantly African-American neighborhood; but I had not focused on these. As I became more willing to explore the totality of my life circumstances, I became more conscious of my "privileged identity" and not just my "oppressed identity."

During this period of awakening and transformation, I was fortunate to have the guidance of authors such as June Jordan (2001), who taught me that oppressed people have to examine their privileges just as often as they grapple with their oppression. Jordan (2001), an African-American woman, described an interaction with a White, female student who declared her (Jordan) to be "lucky" for having lived with oppression. From the student's perspective, dealing with oppression gave Jordan a cause or purpose to her life. Alternatively, this student felt she was "just a housewife and mother," and thus, a "nobody" (p.39). Jordan used this experience to reflect on the ramifications of gender, race, and class oppression. In that exchange, she saw that this student did not see others' oppression as her own cause or her purpose. There was no unity between them as they struggled against gender and race oppression.

Later in her essay, Jordan (2001) writes about an African woman and an Irish woman joining in solidarity to solve a problem, "It was not who they both were but what they both know and what they were both preparing to do about what they know that was going to make them both free at last" (p.44). This was the lesson. I knew my own oppression, but without understanding my white privilege—privilege being the constant companion to oppression— I could not "know" or work against race oppression. If I didn't fully know what others with whom I wanted solidarity experienced, we would be unable to be free of our respective oppressions together.

The Repeating Process of Self-Examination: Conclusions and Lessons Learned

Examining one's own privileged status is a constant process. I have had to continually revisit my tasks as a member of oppressing groups. Freire (1970) called this repeated process of self-examination, "critical consciousness." Specifically, I have to repeatedly remind myself that I cannot expect others to examine their economic privileges if I am not willing to work on owning my white privilege. I knew the vexation that came from waiting for others to accept their class privilege; that economically secure people took for granted their safe neighborhoods, regular meals, and designer clothes always seemed to make poverty worse.

So I planned to appreciate my white privilege, notice it, and then work to extend these privileges to others. For example, not long ago, I was riding on a city train. A beautiful African-American child, about 4 years old, was smiling and talking to passengers. When this little girl and her mother exited the train, a white man with all of the markers of being from a lower-class background made a derogatory comment about the young girl's hair, which had been combed out to a full Afro. I winced to hear his insensitive and disparaging views. He was part of the system of white oppression, a blatant racist asserting cultural dominance based on skin privilege. Only a few moments later, an aging African-American male trudged up the aisle of the train carrying a mop and a bucket. He looked weary, confined to cleaning up the mess made by other people on train cars.

This story is relevant in my transformation because my previous instincts would have been to overlook the obvious signs of race oppression. In the past, I would have mentally felt united with the poverty of the janitor, feeling connected to him by the fact that I had scrubbed my share of toilets, and because my father has been a janitor most of his life. I would not have focused on what I had in common with the lower class white person, or how I personally benefited from systemic oppression based on race. However, this time, I understood in that moment the privilege of being White, and I reminded myself how my race had almost certainly played a beneficial role in my escape from poverty. How many people had just assumed, in part because I am white, that I was bright and easily educated? How often had my "merits" been recognized where they may have otherwise been overlooked if I had darker skin? In that moment, I recognized that I was exceptionally blessed to be riding to a sports event on the train, enjoying my free time, having the funds to pay for leisure, and possessing the capabilities to avoid doing the kind of work that would put that immutable wearied look on my face.

More and more, I recognize that I am fortunate to have had experiences with being disadvantaged. The circumstances of my life have allowed me to develop an empathy that has resulted in deeper interpersonal relationships with others. The weight of oppression has alerted me to the need to participate actively in efforts to change societal injustices. I have come to consider much of what is white privilege as a set of basic rights all people should be entitled to. I am working, through social and political action, dialogue in the classes I teach, and constant reexamination of my self-awareness, to challenge the oppression-privilege dichotomy. There is a certain gift in feeling as if, just maybe, I might be "a part of the solution."

References

Goodman, D. (1995). Difficult dialogues: Enhancing discussions about diversity. College Teaching. 43(2), 47-52.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Jordan, J. (2001). Report from the Bahamas. In M. Andersen & P. Hill Collins (Eds.). Race, class, and gender: An anthology. (4th ed.) (pp. 35-44). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

McIntosh, P. (2001). White privilege and male privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondences through work in women's studies (1988). In M. Andersen & P. Hill Collins (Eds.). Race, class, and gender: An anthology. (4th ed.) (pp. 95-105). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Miner, B. (2001). Taking multicultural, antiracist education seriously: An interview with Enid Lee. In M. Andersen & P. Hill Collins (Eds.). Race, class, and gender: An anthology. (4th ed.) (pp. 556-562). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Reed, B., Newman, P., Suarez, Z., & Lewis, E. (1997). Interpersonal practice beyond diversity and toward social justice: The importance of critical consciousness. In C. Garvin & B. Seabury, (Eds.). Interpersonal practice in social work: Promoting competence and social justice (2nd ed.) (pp. 44-77). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Wade, J.C. (1993). Institutional racism: An analysis of the mental health system. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 63(4), 536-44.

Posted by

DMF

at

6:19 PM

0

comments

![]()

The Third Annual Disability Status Report, the only report of its kind in the nation, reveals that almost 38 percent of people with disabilities are employed, compared with almost 80 percent of people without disabilities. The researchers also found that Americans with disabilities are more than twice as likely to live in poverty

read more | digg story

Posted by

DMF

at

5:42 PM

0

comments

![]()

"Kim" was Native American, an older non-traditional student, and she was from one of the poorest communities in America: a reservation. She came to my first diversity class with memories of her grandmother's stories. Her grandmother told Kim about when she was taken from her family as a small child, sent to boarding schools run by White Christians, and forced to abandon her language and religion. Kim was a bit afraid of white people.

"Tiffany" was a white woman from a rural town in a Midwest state. Her mother was an activist who through her Lutheran church participated actively during the Civil Rights movement. Her mother had been a high school teacher for years now, and shared stories with her daughter of violence and intimidation in the South. Tiffany felt she was educated on racial issues and she was proud to be a feminist.

"Luke" was a white man from Utah. He was Mormon, and deeply concerned about substance abuse. Though his religion forbid using alcohol, drugs, or even coffee (because of caffeine), he knew a lot of people in his hometown who fell into an addiction trap, including some family members. His experience with religious, ethnic, or racial diversity was highly limited, but he knew a lot about how diverse a group of White Mormons in Utah could be. He knew about those who condemned homosexuality, and he could not help but feel a bit judgmental himself. But, he was an avid reader, and he felt he understood the plight of oppressed people. He felt oppressed himself sometimes because of feeling his religion was under attack.

"Derrick" was a Black man. Don't say African-American, he thought that sounded stuffy. He was Black and proud. He was a religious Christian man, but he had also come out as gay about five years ago. His ex-wife and his teen daughter were accepting. They knew he had been trying to live a lie. His pastor had not been accepting, but he recently found a new church that accepted gay or lesbian members.

* * * * * *

Most students at colleges and universities today are required to take a human diversity course. Given that the United States advertises that it is open, tolerant, and brimming with diversity, educated adults are expected to know how to work with anyone. In the field of social work, the urgency of taking this type of class is obvious. A social work student is a professional in training. Professionals like lawyers, doctors, and social workers, abide by a Code of Ethics, and they are usually self-regulated by a professional organization. Typically, professionals are asked to move past personal biases to serve clients without discrimination, but this is a skill and it needs to be learned.

I taught Human Diversity to graduate social work students in a private elite university. On the first day of teaching this class, I looked out at the 30 diverse faces in my classroom, and asked myself, "What are you supposed to teach them?" Should I teach theories of social psychology or sociology about majority-minority group relations? Should I teach a smattering of facts about various groups? Given the emotional nature of the topic, should I just teach students how to talk about these issues without losing their emotional restraint? Sure, I had planned for class, made an elaborate syllabus, scoured for readings that helped people to develop empathy, but I was fearful of a class meltdown. Many people might think that a classroom of social workers-in-training would be homogeneous-- everyone ready to accept each other with bleeding hearts. Nope!

The truth is that I could arrange to have a class exclusively of white Christian women from the U.S. Midwest, and the diversity in the room would likely still be a source of conflict. The older women resentful of how the younger women take gender equality for granted when they put themselves on the line to fight for what improvements have been made since the 1970s. The Catholic women ready to pounce on abortion as a crime against humanity, while the Unitarians are exploding about someone trying to limit their rights. The liberals arguing with each other about whether pornography exploits or empowers women.

I settled on the basics for understanding other human beings: 1) teach students about critical thinking (how to analyze evidence, recognize assumptions, avoid pitfalls of human logical fallacies, etc.); 2) teach students enough history to provide context; and 3) teach students about relationship skills. All of this would mean reminding students that they would be tested emotionally, because this class was about transcending one's own experience and learning to empathize with the experience of others, even when the implications of "understanding" meant challenging one's own bedrock values.

In this type of heated classroom environment, the tiniest disagreement becomes amplified. One student states that everyone in America should be required to know English, and the bilingual students point out that everyone in America should be required to know more than one language. The best approach for handling the differences of opinion was to require students to go through the steps of critical thinking. As I had learned in high school debate, there is great value in being able to articulate perspectives from multiple sides of an issue.

I knew the goal was to help Kim, Tiffany, Luke, Derrick, and the others learn the tools for understanding each other so they could transfer these skills to their professional work. Kim was filled with fear and anger toward Christians and expressed dismay that Native American religions are widely co-opted or dismissed by majority Americans. Tiffany saw Christianity as a moral code that led to her family's crusade against oppression. Luke could not understand how families faced modern pitfalls without the community of believers he depended upon, and any historical problems with Christianity were in the past as far as he could see. Derrick had found support from his Christian faith to face racism, but he knew only too well that not all people were loved by Christians in the way Jesus demonstrated when he spent time with prostitutes.

To provide the actual lesson of diversity regarding Christianity and other religions, I provided articles and lectures on historical background. We read Jewish, Muslim, or other religious authors recounting the Crusades, the Holocaust, and the dessication of the Native religions through "missionary" schools. Next, I provided the framework for understanding how individuals benefit or become harmed by current infrastructure linked to past wrongdoings. Slavery ended approximately 125 years ago, but White people deliberately broke up slave families, so how long would it take to re-create a functional family unit? Many African-Americans learn from studying their history that not only did Whites split their families to prevent a slave uprising, but only decades after the practice ended, the Whites were already complaining about the weakness of the "Black Family." (see Senator Daniel Monyihan's congressional testimony from the 1950s). Conservative organizations were blaming African Americans for a situation that their ancestors promoted.

Being part of a religious majority in the United States means taking for granted that your holidays will be honored by the government, your communities have lots of choices for places to worship, and commercial outfits decorated with symbols of your faith. This was neither "good" nor "bad" but it was real. In private places, students knew that religion was up to individuals, but what about public places? Could Christians learn to share the public space with people of other minority faiths without feeling that they were "under attack" for seeing a Star of David next to their nativity scene next to the city hall?

In the end, nearly every student reported that he or she DID learn a lot of negative things about the dominant culture in many different categories from religion to gender to socioeconomic status, but they were no less invested in being part of the dominant culture. They had new tools for going out and improving it. By virtue of their increased depth of understanding, they listened to each other, empathized, and realized that maturity, development, and growth required shaking up dusty unexamined belief systems.

If you scan the Internet, you can find all of the degrees of human interactions from open conflict and hostility to empathy and support. Sometimes, the weight of the negativity between individuals/groups is disheartening and leads to pessimism about humans achieving peace in the future. However, after teaching this class, I learned that students can learn to appreciate the faults and strengths of their own groups, and they CAN learn the skills to respect multiple cultures.

Posted by

DMF

at

3:08 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: college students, diversity, multiculturalism, oppression, social work

I was a doctoral student, studying the links between poverty and mental health. I worked at a center where dozens of professors, post-doctorate scholars, and graduate students research poverty and mental illness. Yet, I could not breathe normally within the walls of the poverty research center. After I spent time there, I drove home barely able to keep my foot steady on the accelerator; my foot, as the rest of me, was usually shaking badly. The anxiety was not related to the stresses of graduate school or research. It’s just that I suspect any poor person would feel uncomfortable in the middle class surroundings of the poverty center. Some of the other workers with hidden poverty in their backgrounds have vocalized the same feelings. I found this situation ironic.

The people who work at the poverty center are very professional. There’s nothing wrong with being professional, but such customs as dressing formally are difficult for someone from a low-income background. It was subtle, but I have noticed that my less-than-spiffy clothing draws disdainful glances. I wanted to explain that along with growing up on welfare, I have accumulated school debt and personal debt that dissuade me from buying clothes. Money is tight on a graduate student’s budget, and I also had custody of my younger brother and sister. Most of my coworkers did not know the reasons I cannot afford to wear expensive clothes. I wondered if they have ever considered the source of the differences between us.

Apart from the superficial differences between myself and my coworkers, there are mannerisms and social mores that I tried, often unsuccessfully, to emulate. I lived in fear that my customary style of speech, sense of familiarity with strangers, and my brand of humor will slip through my facade. For example, my younger brother was awaiting sentencing for drug dealing. When my mother and I created his birthday greeting, we enclosed a Monopoly© “Get out of jail free” card. When I shared what I considered to be a clever idea with colleagues, they appeared mortified. It was clear that they did not understand our sarcasm, and they expected the poor to be humorless about their adversities.

When I did show a behavior more common to someone with a disadvantaged background, the tension in the room rises. For instance, there is a norm in scientific research centers to discount personal experience as a source of knowledge. Most of the people I know from my background value the personal account as a means of understanding. So, when someone in a seminar mentioned a “fact” about Head Start that was not true in my own Head Start experience, I voiced my dissenting thoughts. Because my comment was based on my own experience, and not on a statistic I had memorized, there was a moment of silence in the room. The conversation moved on with no further mention.

A poverty research center with an atmosphere that is jarring to a poor person’s sense of safety is a cause for concern. I strongly feel that social workers—in research or in the field—should make every attempt to create safe environments for people with different backgrounds. Furthermore, I question whether the knowledge of poverty my coworkers had gathered through books and journal articles was any more valid than the first-hand knowledge I had gained. Although I was new to feminist theories, it was my understanding that one school of feminist thought has come to value the “ways of knowing” that come from personal experience. I do not ask to dominate the knowledge base concerning economic disadvantage, because I understand that my experience cannot be generalized to others. On the other hand, it is my conviction that my insights could add to the conversation.

I have never been asked to be an expert speaker for a class studying poverty.

The longer I stayed in graduate school, the more convinced I became that I will never be asked to speak on poverty. Was I qualified to give such a talk? I think so. I do not remember a time when my family was not utilizing public income assistance, at least through food stamps. Actually, this isn’t quite true. During my fifth grade year, my family became ineligible for public welfare when aid to two-parent families was cut. As a result, we did not have heat in the house or regular meals. The Department of Social Services took custody of myself and my four younger siblings, because my parents were judged incapable of providing basic needs. Our foster families were paid a subsidy to care for us--financial assistance that far exceeded the monthly allotment once given as welfare to two-parent families.

Recently, speculation ran high in one of my classes on poverty. They were debating what will happen to families following welfare reform; I believed the discussion could be informed by my own life account. Unfortunately, I chose not to share anything personal, because I then understood the disinterest this type of contribution will face. Instead, I did speak up about the statistics I had heard or the theory I had read. This type of comment was accepted with nods of agreement; I guess everyone is on familiar territory when social work academics remain in the world of cold facts.

There are other sketches of poverty I could offer. I have spent a fair share of time in homeless shelters with my family. Some of the correlates of poverty, including divorce, domestic violence, mental illness, or substance abuse, have been regular occurrences in my background. Furthermore, I could speak to the toll of poverty on one’s mental health. I am pleased that data analysts show interest in the statistics about poor people. It is heartening for me to see many social workers go to areas of economic disadvantage to provide services. However, social work researchers and practitioners need to be conscious that a short-term brush with the poor is not equal to understanding their experiences. It is problematic when social workers begin to speak “on behalf” of the poor, without being inclusive of the people themselves.

During my junior year of college, I was interviewed in a focus group of people raised poor. Although some statistics indicate that a childhood spent in poverty is overcome once a person enters college—and thus the middle class—I can tell you there was terror in that focus group. We all recognized lasting effects of worrying about food or shelter. Our sense of self was impacted, because many of the group members mentioned feeling isolated from other college students, and inferior to people in general. Everyone in the group was unable to shop in standard shopping malls; we each felt as though the store help could recognize us as poor people, and thus they would suspect us of stealing. The list of similarities in our anxieties, and our diminished sense of self, was not coincidental. We all knew that poverty had taken its toll on our mental health. As yet, I have not found a single senior researcher interested in collaborating to investigate this phenomenon. Maybe this type of investigation into poverty is based too strongly in daily experience. In the course of day-to-day living, poor people encounter prejudice, discrimination, and pity. This type of experience is emotional in nature, and emotional reactions to poverty are not of interest to researchers. Poverty researchers study observable behaviors of the poor, such as teen pregnancy, joblessness, and criminal activity.

I cannot speak for all poor people, be they currently poor or living with a history of poverty, but I believe we should be given a voice with regard to our life experience. I have been in social work classes where a student dominated the conversation by giving a lengthy description of their personal circumstances; sometimes, these students seemed to be seeking a brief in-class therapy session, or they wanted to show their superior understanding of a topic. There are many ways to use life experience, and like any contribution, there may be abuses. Nonetheless, if research or in-class training included more information about the daily lives of poor people, middle class social workers might feel more comfortable interacting with us in class, in therapy sessions, or at poverty research centers. Poor people like myself could begin to feel less like objects, and more like contributing members of the academic world. How do thoughtful people who have not been poor best relate to those who have had such experience? They could begin by looking at their personal and professional relationships.

Posted by

DMF

at

2:55 PM

0

comments

![]()

Today I am celebrating my 32nd birthday. I look 22. I have been asked to produce proof of age for purchasing alcohol as recently as a few months ago. Lucky me. However, I feel 52. No one can tell my background by looking. Not-so-lucky me. Mostly, I bear invisible signs of being broken down. I have had back surgery, heel spurs, arthritis, major depression, anxiety, and endocrine problems. An untreated ear infection during my youth has left me with impaired hearing. Poor nutrition has led to more visible signs of a broken body--bouts with obesity and broken strands of poorly nourished hair. Then there are the prescriptions I need for my peace of mind: an anti-depressant and an anti-anxiety.

1980

My 4th grade class voted in a mock election. I voted for Ronald Reagan. In the real election, my parents voted for him as well. At the time, my father worked full time as a maintenance man, and my mother worked part time as a substitute K-12 teacher. By 1981, my father was laid off from his job. Once his unemployment benefits ran out, we survived on my mother’s work. As the unemployment rate climbed and competition for jobs rose, my mother was called less and less frequently to teach. My parents were not too worried at first. They were confident that the new president would change the economic tide with his trickle down strategies. As time passed, and our economic situation became more ominous, my mother called the welfare office to see if our family could receive assistance. The answer was no. Government policy was that welfare only be given to single parents. In fact, what aid had been available was being cut under Reagan’s economic plan.

Slowly, our family began to curtail spending on things like clothing, heat, water, and finally food. I got my first job in 4th grade. I was nine years old when I became a Des Moines Register newspaper carrier for half of the town of Denver, Iowa. The paper delivery business had been okay in the summer, but as the air grew steadily colder I began what would become my lifelong fear of winter. I’d bundle up in several layers of sweaters, put on heavy boots, and pull on a parka. Each day, I walked about two miles to deliver all of the papers. The exertion from lugging pounds of newspaper taxed my lungs as I struggled to breathe bitterly cold air. The warm, exhaled moisture in my breath made my scarf damp, which in turn, led it to freeze. My mittens never kept my fingers from freezing, and my multiple layers of socks did not save my toes.

When it was extra cold, my eyelashes froze together. Sometimes, I would need to pull my eyelashes apart just to be able to see. Whenever this happened, I became scared. A Des Moines Register paper carrier had recently been kidnapped. I felt safe believing I could fight off any attacker if I could just see him. It was not easy to maintain this bravado being a young girl walking alone in the dark before sunrise. However, I was keenly aware that my contribution to our family’s income was critical.

1981

My younger brother and I got off the school bus at the end of the day on December 18th to find a police officer. He put us in the back seat of his car and told us he was taking us to the hospital without explaining why. During the 12-mile drive, I remember clearly being convinced that my parents and my preschool siblings must have died in an awful car crash. I squeezed my brother’s hand and whispered that I would take care of him. Inside, I was petrified.

Fortunately, I had been wrong. My entire family was alive. They just were not going home together. Child welfare workers were responding to reports that my siblings and I were being “neglected.” When they arrived, the temperature in our house was 38º, except in one room where we all lived around a wood burning stove. The water pipes had frozen at some point. They found our food supply consisted only of canned vegetables taken from our garden that previous summer.

“Mr. and Mrs. Bad Parents, we need to talk to your daughter privately. The officer outside will bring you to the lobby area.”

My parents were not recognizable, because they behaved like obedient children. I was unaccustomed to seeing my parents taking orders. The bearded man told me to take the seat my mother had vacated. He settled across from me with a clipboard. The female police officer sat in a corner of the room.

“Did you eat breakfast today?” he asked quickly.

What a weird question, I thought. I was getting warm in my winter clothes, but my feet were wet and cold. I curled my toes tightly together as I considered his question. But past experience told me that I should answer yes. Grandma and grandpa would also ask this question whenever I went to stay with them. Mama and dad told me to always answer affirmatively.

“Yes, I had cereal, and eggs, and bacon,” I lied.

“Does your family have a refrigerator?”

“It stopped working. We keep things outside to keep them cool.”

“Where do you sleep?”

“I have a mattress in the basement. Why are you asking me these questions?”

“Your parents left your sister and brothers alone at home. They can’t do that. I want you to tell me honestly about how they take care of you.”

I did not like this man with a complete mane of hair around his face. He scared me, and I resented how he talked about my mama and dad.

“Okay, you said you had bacon and eggs this morning. How did your mama cook these for you?”

“We have a hot plate. It’s like a mini stove.”

“Hmm, well, your house does not have any electricity, so how did the food get hot?”

I could only glare in response. At that point, a man wearing a white-coat opened the door. He was obviously a doctor. “I can examine her now,” he told the hairy man.

He held my hands in his, carefully looking at my fingertips for signs of frostbite. He then asked me to remove my boots and socks. I did so unhappily, because I was concerned about my toes never warming up.

1982

I did not like living in the city. Waterloo, Iowa sounds small. It is, but for a rural state, it is the big city. My parents moved there, into government housing and in exchange, the State returned my brothers and sister and me. Eventually, when my parents divorced, the courts calculated my father could afford to pay $75 a month in child support. My father never missed making his child support payments. I delivered my morning newspapers on a new route. It was the city, so it seemed scarier. Now when my eyelashes froze together, I would panic and feel like screaming. Still I told no one of that old fear of being kidnapped. We needed the money.

It was time to go shopping for school clothes. I lowered my head, so my chin touched my chest. Hugging the storefront window as I walked toward the entrance of the second hand clothing store, I allowed my mother to serve as a barrier so that I would not be seen.

“I hate coming here. Someone will see me, and they will tell everyone in school,” I hissed to my mother. “This is going to be my first year in middle school, and I don’t want it to be ruined.”

“Anyone who sees you here must need to shop here as well,” she reasoned.

“But that won’t stop them from driving by and seeing us here.” I slipped into the door, relieved to be off the street. Although I did not want to shop in a secondhand store, the excitement of potentially finding fashionable clothing became the focus of my attention. I left my mother in the shelves dedicated to outfitting young boys, and headed for the girl’s clothing. At the circular racks of clothing, I pulled apart two shirts to allow a full view of an eye-catching red shirt. There was a large stain on the lower right side of this otherwise stylish shirt. In disappointment, I moved onto the next few items. Critiquing each shirt, I passed over most of the selections. There were two shirts and a dress that looked like they would fit in with what my classmates were wearing. In particular, there was a long-sleeved, pastel yellow t-shirt with rainbow colors on the sleeves, like a baseball jersey. This was a rare find, because shirts like these were considered quite popular.

At the changing room, I found that the shirts stretched tightly around my chest. Frustration built as I realized these items did not fit. Revisiting the clothing racks, I spent over an hour looking for other decent clothes. My mom and I left after spending $4 for a skirt and two shirts for me, and a few dollars for my brothers’ clothing.

The next day, I adorned myself with a pale green shirt with small flowers. I put on my new skirt, an ivory fabric with large yellow flowers. I was excited about having new clothes, and I had just gotten new white tennis shoes to top off the outfit. My clothing may not have been name brand, but I felt more confidence from my feminine look. To up the ante, I added sky blue eye shadow and plum blush to my face. It was 1982.

In Mr. Lincoln’s classroom, I spent every afternoon learning social studies and English.

“You look nice today, Deborah” said Mr. Lincoln. I felt a rush of pride. The fact that this nice teacher had noticed my appearance made me feel attractive.

During our lunchtime recess, several girls who were considered popular approached me. For a second, I was exhilarated; obviously, they were coming to include me in their clique, because I had new clothes.

“Where did you get that outfit?” Dawn sneered. “It is so ugly, and it does not match.” She was wearing expensive jeans with a pink polo shirt. Her light blonde hair was feathered back from her face. Like Farrah Fawcett.

Dana chimed in to say, “You need to tell your mom to buy you a bra, because you are totally drooping.”

Finally, another member of the group pointed to my shoes. I don’t remember who she was, because I could not lift my eyes to their faces. She declared, “Those came from a secondhand store.”

“They did not. My mom bought them at JC Penney’s,” I protested.

“You liar. I think my mom donated them last week,” she responded.

Dawn, the undisputed leader of this girl group, concluded their sentiments by saying, “You always smell bad. It sucks that my locker is right next to yours. I doubt you will ever have a boyfriend.”

I didn’t bother to respond, because of the lump in my throat. I spent the rest of the day staring at the ground, not sustaining enough energy to keep my head lifted. On the way home from school, Dawn and her friend Dana followed behind me.

“You’re a loser, and we are going to kick your butt.” Despite my fear, I told them to leave me alone. Another girl was walking down the grass on the other side of the road. She called out, “Is everything all right?” She hastily crossed the street, and stood beside me. I recognized her as the girl who belonged to a strange religion. She was required to wear a dress or a skirt every day, and she could not cut her hair.

Dawn and Dana whispered about both of us, making snide evaluations in audible undertones. Nonetheless, they walked away, leaving me with my savior.

1983

We moved out of government housing. We moved to a new school district. Again. It was 8th grade. We were evicted quickly for inability to pay rent. The night of the eviction, my mother took my siblings and myself to an all night diner. By the morning, the manager, or maybe the waitress, had called the police. They escorted our little weary family to the homeless shelter. The sun was coming up. but I was ready for sleep.

So, we moved again. To the African-American side of town. A few days after moving in, a light-skinned girl approached me as I hung our family’s laundry on the backyard clothesline.

“Hi, my name is Gayle. My next door neighbor Brenda told me you just moved into the neighborhood. Where did you live before?”

Somewhat guardedly, I responded, “I lived in public housing on the West side, over by the high school.” I skipped telling her about the 3-month stay in a rental house. Rather than looking at her, I continued to keep my gaze on the clothespins.

“I know someone who lived over there. Those are nice places…how come you moved to the East side?” Gayle was continuing the conversation, a surprising development. I was unaccustomed to having truthfulness about my background met with acceptance.

“My mom did not like the monthly inspections of our apartment. The managers yelled at her for storing pots and pans in the oven. She wanted to get our own place, before they found a reason to kick us out.”

“Well, are you going to be done with the laundry soon? I want to introduce you to my friend. How come you have to do the clothes washing anyway? By the way, your house has bats.”

Before I went to talk with Gayle and meet her friend, I examined my appearance in the panel of mirrors across our living room wall. A wave of anxiety passed over me as I realized my potential new friend had seen me in red polyester shorts with a see-through blue cotton shirt. My hair had been uncombed, and old eyeliner blackened the area under my eyes. I quickly changed into a denim mini skirt, and a polo shirt. I made sure I put the collar of the shirt up, because I wanted to show that I had fashion sense. Running a comb through my hair, and using tissue to rub away the eye makeup, I felt I looked presentably. Gayle and a heavyset black girl sat on the concrete steps leading to Gayle’s front porch. I took in her glistening Geri curl hair style.

“She has no ass, and she ain’t gonna have much luck getting a man,” the unfamiliar darker skinned girl told Gayle immediately. She made no effort to keep her comment from my ears. Turning directly forward, I swallowed, and blinked away tears. These girls would be no different than the girls who taunted me at the last school. I used my hands to cover my backside, ashamed of my flat bottom.

“But ya know, she got good legs, and big boobs,” she continued. I stopped short, and with shakiness in my words, said, “Why don’t you like me?”

“Aww, girl. I can’t say yet about liking you. I’m just telling’ what I see. I got a few boys in mind for you. A couple of cousins.” We were thirteen years old. A few months later, she went with me to get birth control pills from the free clinic. We were being responsible, but the nurses lectured us. They didn’t understand that we could not risk getting pregnant. It could make us stay poor.

1985

Gayle went away for the summer last year and left me to work. Not this year, though. I was going to go with her to Luther College for the summer, taking classes, meeting other kids like me, and maybe making friends. I was accepted to Upward Bound, a government program that assists low-income high school students with attending college by providing college prep experiences. This program was going to save my life. I met friends, began to crack the armor surrounding me. Old notes I read from my file say, “She is really coming out of her shell.”

The Upward Bound summer was supposed to last for six weeks. My family desperately needed money, and the middle weeks of July offered the promise of jobs working in the cornfields. For two to three weeks each summer, people earn minimum wage helping to create hybrid corn. With the opportunity to earn money, I left Upward Bound for two weeks, regretting intensely my need to leave. With my field work money, I bought my family its first car in four years—a 10-year old bright yellow, but very rusty, station wagon. It was an investment that would allow for more employment.

Posted by

DMF

at

4:06 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: first-person, memoir, poverty

Growing up Lutheran, my mother went to New Guinea on a Lutheran mission in the late 1960s. When she returned, her family, including her domineering father, had converted to the LDS church (Mormons). She dutifully followed suit, and traveled to Salt Lake City, Utah to absorb her new religion. When church elders told her that God had informed them she belonged with my father, she married him. The drumbeat message to be a good mother consumed her, and she had six children as part of her understanding of what Church leaders expected of a good Christian woman. She called feminists, "libbers," condemned abortion, and embraced traditional roles for women: wife and mother.

When my parents met seemingly even more devout Mormons, specifically fundamentalists, they were enamored. A time-limited (Thank God) saga involving polygamy ensued. After realizing that she had been led astray by false prophets, my mom went on a quest to find God's church. There was a period where both of my parents held home "Sunday School" with us: teaching Bible stories, drawing Biblical events, and learning right and wrong. Then, there were months, sometimes years of membership in churches such as the Vineyard, Seventh Day Adventists, Christian Scientists, Methodists, Baptist, a brief Jewish exploration, and several others I can no longer remember clearly.

My tremendous, yet vulnerable mother is truly one of God's children. Unfortunately, her reluctance to question those "authorities" who claim to speak for God, left her prey to the worst kinds of fanatics. She became overly obedient, failing to exercise independent thought or judgment. When indoctrination becomes severe enough, even the conscience can be usurped. Her own struggles to make it right with God mirror what a great many American Christians are presently doing. They are following fanatic leaders who lead them astray from what Christianity really means. The following website contains several examples of people who are clearly raising themselves above others and acting contrary to the teachings of Jesus:

http://www.reandev.com/taliban/

For all of my mother's problems with organized religion, including the times when she put aside her judgment, she has maintained a personal spiritual integrity that I realize shaped my own beliefs about right and wrong. One lesson is particularly salient. Refusing to reject anyone, she befriended a male-to-female transsexual person when I was in high school. They met at the Salvation Army where our family ate lunch every weekday but Wednesday when the soup kitchen was closed. In our small Iowa community, people with differences stand out, and this person had a number of barriers to gender resolution. She clearly felt like a woman, but she was poor and could not afford surgery. Thus, she grew her hair, wore a padded bra, and wore women's clothing. Without hormone therapy, she had a visible five-o'clock shadow, and her body was stocky even by male standards. Her situation led to ridicule throughout the community.

When mom requested that this person pick me up from school, I was humiliated. I tried to slink into her car without being seen by peers. It didn't work, and several days of I already dealt with the stigma of being poor, and there was several bullies at the school who had targeted me for years. They would taunt me about my clothing, my outdated hairstyle, my cleanliness and associated "alleged" smell, etc. Once I had a chance to confront my mother, I asked her why she tortured me by sending this person to pick me up from school.

She told me that a good Christian looked into the souls of others and offered them Christlike love if they were good people suffering with adversity. It was not her place to judge, to criticize, or to demean. She told me that I should be ashamed of myself for letting the cruel, childish opinions of others influence my own treatment of others. She was right. Pure and simple.

http://www.sojo.net

Posted by

DMF

at

3:42 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: christianity, kindness, love, religion

A girl aged 11 hanged herself in a Philippines shanty after leaving a letter and diary depicting a life in rampant poverty, newspapers here reported Thursday.The case put a human face to poverty blighting the nation, where nearly 14 percent of the 87 million population live on less than a dollar a day.

read more | digg story

Posted by

DMF

at

11:30 AM

0

comments

![]()

When teaching about multiculturalism, instructors often ask members of oppressed groups to offer one or two examples of statements they never want to hear again about their social group. Growing up in what some call, “the White underclass,” (Hartigan, 1997), I have accumulated a substantial list of poverty stereotypes that I would love to ban. However, opinions about poor people, unlike those spoken about other groups, are considered a matter of political belief--and derogatory comments are merely seen as free speech. The radio and television airwaves are presently dominated by rhetoric against poor people, but such talk goes largely unchallenged. The taboos against speaking about American classism are difficult to overcome. There is little language to discuss what classism is, and many do not know how it is institutionalized in our schools, churches, government, workplaces, and attitudes.

Lott (2002) defines classism as discriminatory institutional and interpersonal responses to poor people and poverty by those who are not poor. Like racism or sexism, classism is based on devaluation, exclusion, stereotyping, and prejudice, with the target being poor people (p. 100). Individuals from middle and upper class backgrounds have power, defined here as “access to resources paired with the ability to set social rules” (Lott, 2002, p.101). Like racism, where White people by virtue of their ethnic features, have access to resources and the ability to define social structures, classism confers social and economic advantages to people with resources.

In this thesis, I attempt to provide examples of classism while also discussing the personal cost to individuals and society when classism goes unacknowledged and unchallenged. I will also explore how the structure of higher education plays a role in perpetuating classism, as well as social and economic inequality.

A Personal History of Harm by Classism

I come from the White underclass, estimated to include just fewer than 2 million people, mostly children, in the United States. Various scholars have defined us differently, but some features of the White underclass are: 1) concentrated neighborhood poverty, 2) high rates of family dissolution or single parenthood, and 3) long-term use of welfare (Murray, 1986). I have been a foster child, something that occurs for only about a half a million children a year. I have also been homeless—twice. Conservative policy makers like Charles Murray, a man with an established history of romantizing poverty (see his 1988 essay, “What’s so bad about being poor?”), sounded the alarm in the mid-1990s that the white underclass was a looming threat.

My hometown neighborhood was identified in U.S. News and World Report as the 7th largest white ghetto (Whitman & Friedman, 1994). Relative to others in the lowest income quartile, our family, with an annual income totaling approximately 30-50% of the poverty line, was considerably poorer than most. It is difficult to understand the poverty line without a reference and even more difficult to summarize the economics of a family over the span of many years. So the best way to explain our family income is to say that throughout most of my childhood, my two parents and their six children on average lived on approximately $5000-8000 per year or $400-$650 per month (in 2004 dollars). Paying rent usually took 75% of the cash our family had, leaving about $12.50 per person per month for all other expenses aside from housing. We had no assets whatsoever, but rather carried a constant rolling debt with creditors who gauged poor people with usurious interest rates.

Seven percent of people in the lowest income quartile in the United States get a Bachelor’s degree by the age of 24 (Mortensen, 2001). Statistics on the number of Ph.D.s given to people from the lowest quartile are not readily available, but poor people are scarce among professors (Oldfield & Conant, 2001). Needless to say, a tiny percentage of people from my background are university educators.

Getting an Education

No one suspected I was heading for doctoral studies during my childhood. My first and second grade teachers from a small town in Iowa identified me as “slow,” because of irregular gaps that appeared in my early basic skills education. My early schooling had been quite chaotic, so despite participating in Head Start, I was still behind. Economics had led my parents to move more than 100 miles in pursuit of jobs—not once, but three times—in the late 1970s, during my kindergarten and first grade years. These teachers who labeled me as slow also expressed disapproval of the way my parents were raising me. At one point we were all ashamed when they figured out that an ear infection had caused some hearing loss because my parents had not been able to afford medical care for me. Their disdain was made obvious in their verbal comments about the threadbare nature of my clothing, my disheveled appearance, or other types of derogatory remarks they made on my report cards.

My third grade teacher reversed my prior intellectual assessment and labeled me as, “talented and gifted,” which opened new doors to me in terms of classroom and educational experience. Through this program, I learned a few skills on an Apple computer during a time when most elementary students were not introduced to computers at all. During 4th and 5th grade, I escaped from the stressors of school and work—yes, work—by reading constantly: in the bathtub, on the way to school, in the sliver of light under the door after bedtime. Beginning when I was age 8, I had a job each morning at 5 AM delivering Des Moines Register papers to half of our small town. I worked outside the home consistently in some form of employment from that age onward.

Many of my elementary school teachers made negative assumptions about my low-income parents including the belief that they were “druggies.” Their opinions became apparent during my 5th grade year when the State of Iowa conducted a child neglect investigation after they found our farmhouse was 38 degrees Fahrenheit. My teachers went on record to share their guesses as to the sources of my parents’ lack of resources, and substance abuse topped their list of stereotypes about what led to our poverty. In reality, neither of my parents ever touched a drug or drank alcohol. The difference between the assessment provided in the 35+ pages of the child neglect report and the reality of our family life is so striking that one immediately sees why child welfare agencies have such degraded reputations.

Instead of being “potheads”, both of my parents suffered from major mental illnesses (e.g., schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) where their symptoms were expressed as zealous pursuit of religious enlightenment. This actual situation of an exceedingly religious milieu was never described in the child neglect report or noted by the investigator. When I look back at this report, and think about the social services employee who failed to even come close to accurately evaluating our family, I wonder about the extent to which his classism was to blame. He saw poverty and assumed substance abuse. He built a case around a myth.

In any event, my youth was characterized by interactions with strict religious sects and conservative Christians rather than any sort of hippie drug culture. I was the child never allowed to watch TV, participate in Halloween, or play with even mildly rebellious children. My mother had to be convinced by repeated displays of desperate pleading to allow me to attend school. She preferred the idea of home schooling where she could maintain the Godliness of our learning environment. She would hate to hear this, but that type of Godly atmosphere had its significant drawbacks including terrifying her small children whenever there was added talk of demons and Satan. Still, we were a very close family with strong bonds of love built on a foundation of Biblical teaching.

Based on the interventions for poverty and unemployment selected by the State in 1981, my family life changed entirely. Their choices included 1) placing my siblings and myself in foster care to protect us, 2) securing public housing for our family to relocate to an urban area, and 3) finding my father a minimum wage job in the same blighted urban area. The State selected these interventions based on established social policy, and social policy is determined largely by the values of the people. Rather than offering a temporary cash payment to my parents in the form of welfare, the State was only willing to address our poverty by splitting up our family and paying foster families over $1200 per month (in 1981 dollars) for the care of the children. We never would receive such monetary support for keeping our family united.

Assumptions about sinfulness, poverty, the Puritan work ethic, and other American traditions had led to miserly social policy that left almost nothing of a safety net during a period of high unemployment in the early 1980s. During that same time period, the invisible nature of mental illness in the national consciousness, and the lack of services to families affected by it, meant that the root of our poverty was never actually addressed. There were no mental health policies to assist parents with major mental illnesses in parenting or securing income for their families. I would later learn during graduate school that President Reagan’s policy changes directly led to reductions in the types of interventions available to the State of Iowa at that time. Realizing that my family was split apart by poor social policy, I was drawn to studying policy analysis from that point on.

Prior to the government’s intervention, my life was dominated by family activities such as tending the three gardens on our farmland—because they were our sole source of food—involvement in family Bible study, and performing family community service such as cleaning up litter in public parks as a substitution for monetary tithing. My parents could not afford to tithe, but they wanted us to do our part. Perhaps the best evidence for the strength of my parents’ love and attention comes from the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills administered yearly to youth across the country. Each year, 5 of 6 Megivern children received letters from the superintendent of schools congratulating us for scoring in the top 3% in the country.

After the Government “Helped”

By and large, before the government stepped in to help with our poverty, I was a healthy, developmentally appropriate child with a high sense of security despite long-term familial bouts with unemployment. After the government’s 1981 intervention, my parents’ ability to function deteriorated and became inconsistent. The stability they had always provided, even within the confines of poverty and mental illness, was now dissolved. Both parents became paranoid, fearful of the State and its power to take away their children, fearful of the economy that could leave them unemployed for such long bouts, and finally, fearful that God had abandoned them. The structure that had previously characterized our lives was replaced with an unpredictable schedule and limited parental interaction. I babysat for my siblings while my parents worked different shifts at minimum wage jobs. Bringing together the full family unit was never again easily done. My youngest sibling, representing 1 out of 6 Megivern children, was born into this post-intervention environment, and he never scored above the 35th percentile on the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills.

A particularly dark memory from the period around my 12th birthday haunts me and helps to maintain my deep fear of the Police. My parents were working a great deal, and I was babysitting on a constant basis. My ten-year-old brother David was being beaten in another part of our public housing units by a small group of boys. I left my younger siblings with my next oldest brother and went to try and rescue David. Shortly thereafter the police arrived, and in sorting out who did what, a malicious officer—who liberally utilized social class slurs—filed a child neglect report on me. After all, I had left my siblings in the care of an 8 year old. The State found me guilty of child neglect when I was 12 years old without listening to my story and without providing me with any representation. In retrospect, the knowledge that a middle or upper class child would never have been treated in this manner deeply angers me; more so, because I was made to feel ashamed about a situation that should instead be a source of shame to society.

To this day, I keep and archive several inches of documentation on the involvement of child welfare and social services in our family. Some of the assessments they made were so ludicrous, they deserve to be scrutinized by the government as a means for improving services. For example, the documents following an inpatient psychiatric evaluation of my brother Daniel when he was 14 years old include predictions that he would “only become a future master criminal.” Currently, he is a law-abiding electrician for Quaker Oats in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. To be poor and distressed meant being labeled dysfunctional in a menacing manner even when demonstrating behaviors that would be considered normative in any child under severe stress. Poor children are not like other children, almost as if they are bad seed.

As a highly parentified child after my father and mother divorced, I was controlling the finances for my family by the time I was 14 years old, and I knew that we were in dire circumstances. In 1987, when I was 16, my mother attempted suicide. To prevent the State from learning that we were unsupervised, I quietly called on extended family for help and missed school to care for the preschoolers. Luckily, the social programs that were effective for me—such as a government educational program called Upward Bound—had staff members that never treated me using “professionalism.” They took midnight phone calls for help, provided personal assistance well beyond the end of the program, and intervened even when policy tied their hands.

One of the ways that middle and upper class people exercise their authority and “help” without really helping is through codes of “professionalism.” The professional person dresses in a business uniform, keeps small talk superficial, and never politicizes their personal experience or that of their clients. Among many poor people, “professionalism” is actually a simile for upper class. Keeping low-income children with a history of adversity and trauma, “at arm’s length,” is easily a contributing factor to the ongoing distance between helping professionals and the poor. A professional assists or studies poor people “at a distance.” A professional does not really care about you, but is paid to intervene in your life.

Upward Bound was not a social services intervention in the traditional sense. It was a holistic setting where youth could grow and heal. Among poor people who have gone through the Upward Bound program, there is wide agreement that this type of educational and supportive intervention would truly start to help children rise from poverty through education, but it is available to less than 10% of poor youth.

Going to College to Escape Poverty

My duties in helping my mother to raise my younger siblings were so unambiguous to me that I nearly did not attend college. I enrolled at Luther College, a Lutheran liberal arts school in Decorah, Iowa, because of, Project Upward Bound. I also ended up making it through college with the help of this federally funded antipoverty program.

During my first year of college in 1989, my interest in learning about how poverty affected identity and mental health led me to research psychological databases using the keywords poverty, inequality, and identity. In particular, I wanted to learn how to feel less marginalized among other college students, and somehow less bitter about their significant unacknowledged privileges of safety, security, free time, and childhood. There were no articles, book chapters, or edited volumes on the topic. Repeated literature searches each year since then have resulted in a smattering of articles from across many academic disciplines. As an 18-yr old, I remember thinking that the percentage of poor people in America must be low, or else someone would have thought to write about poverty from the psychological perspective. What I did not realize was that one in five American children is poor, but talking about social class and poverty is largely forbidden in America, unless you were complaining about how high taxes had become due to welfare queens.

One of the most damaging socioeconomic experiences was attending school with privileged students—who appeared more intelligent, educated, and superior because they had more access to resources— talk as though they had worked hard to get where they were. I worked 30+ hours a week off campus and 10 hours a week on campus throughout college (1989-1992) with the exception of a semester where I was privileged to study in Germany due to the generous donations of the college. My work shifts were difficult, because I ended up typing all of my papers on a typewriter between the hours of midnight and 6 am. I had no choice but to use a typewriter in the computer age, because the campus computer lab closed before I got off work. Worse than the disconnection from others socially was the feeling of resentment over my decaying health and mental health as a price of extreme adversity while I watched wealthy sorority and fraternity youth vomit hundreds of dollars a week in alcohol on Thursday-Saturday festivities. Well, I did not just watch, but rather I served them.

Studying poor people

I went to graduate school to study how poverty affects individual development. I soon realized that poverty research is done in a very specific manner that I felt objectified those from poverty communities. In addition, the focus was not on the people, unless it is about their pathology. Typically, the focus of poverty research is on large social trends or specific African American communities.

I was a child of the 1980s, turning 30 in the 21st century. The poverty we experienced was eclipsed by the glaring wealth, excess, and widening inequality of that era. We are not represented in the media, in research, in the literature, or in the minds of the American people. Only about 1.7% of white children is extremely poor for greater than 10 years, but that means there are approximately 2 million of us, rivaling rates of schizophrenia in the American population (about which there are multiple journals, let alone articles). Where are we represented in scholarly investigation?

It has felt as though if I would suffocate if I could not find my voice, a voice for poor people, including those of us who are white, in the sanitized academic environment. I began writing about poverty and classism in a short piece called “The Poverty Experts” in a student journal, Social Work Perspectives, where I told about the lack of acceptance of poor people evident in poverty research. I almost dropped out of graduate school, feeling very isolated and different. Most of the researchers are middle class and they would feel uncomfortable around poor people. They were always a bit nervous with me. This amuses me, because I am fairly good at not being too stereotypically underclass in my behavior. Plus, I am widely regarded by poor people as warm, friendly, and easy to be around.

Crawling Across the Ph.D. Finish Line

Throughout most of graduate school, I raised my two adolescent siblings: taking out high educational loans, charging food to credit cards, and working as a teacher’s assistant, research assistant, and a gas station attendant to support our small nontraditional family. My adolescent sister had two suicide attempts and two psychiatric hospitalizations while my youngest brother dropped out of high school despite many interventions I attempted. They were both more highly affected by the trauma of foster care and its aftermath on our family unit, perhaps because they were small children when the most chaotic experiences occurred. My next oldest brother David committed suicide in 1997 by hooking a vacuum hose to his car exhaust and winding it back into the car. He had attempted college, but returned after a semester significantly depressed. Our whole family knows he died because of his socioeconomic life experiences and classism.

I completed my dissertation with a herniated disk in my back that can be traced to the paper route I had from age 8-12. The heavy bag of papers was always slung to my right side, pulling my back out of place. The price is paid so much later; I did not know how my work would hurt me as I aged. I still have chronic cold hands and feet from the frostbite I sustained during the winter months of paper delivery. None of these life experiences is particularly extraordinary until you compare my life with that of my classmates in college and graduate school. Others in their early 30s could not fathom the kinds of experiences children have in “the Other America.” Hopefully, the strain of my socioeconomic ascent becomes easier to contemplate for privileged individuals when they can take an insider’s perspective on psychological and emotional reactions of poor people to encountering others taking a blind eye to their own advantaged background.

Immediately after defending my dissertation in June 2001, I began my postdoctoral training in a condition of coping fatigue. I was drained from dealing with years of chronically high stress, but I needed to complete my dissertation and meet the demands of a research center, so there was little time to recuperate. Unfortunately, the effects of poverty do not take a holiday just because I was solidly middle class as a doctoral research professional.

During my postdoctoral years, my father began a two-year saga with an open head wound that still has not healed in 2004. There is a website with pictures for those interested:

Consequences of Lack of Health Insurance

They have taken skin grafts from his thigh to try and heal him, but it has been too late. Years without health insurance meant that his severe and untreated diabetes created a chronic distressing health situation. It was painful to me when he was unable to travel to my wedding in 2003, because of a health problem that may not have occurred had he had access to health care earlier in life. I have an endocrine disorder related to diabetes, and I had hoped to focus on this aspect of my health through concentrating on my physical fitness during my postdoctoral training, but instead I needed to take additional time to recuperate from back surgery. At least, I could finally afford to have my back fixed, because I had health coverage.

I cringe to realize I still pay the price for growing up poor through suffering current psychological burdens that affect my productivity and competitiveness. I am a middle-class professional, but I cannot afford to help him or others in my family. Low-income students do not educate their way out of poverty, but rather they buy their way out of poverty by taking out high educational debt to earn access to the American labor market through credentials. It is not supposed to matter to me that other children are simply given these advantages. The helplessness I feel in trying to help my father financially is deeply detrimental to my well-being.

Higher education replicates inequality