The Third Annual Disability Status Report, the only report of its kind in the nation, reveals that almost 38 percent of people with disabilities are employed, compared with almost 80 percent of people without disabilities. The researchers also found that Americans with disabilities are more than twice as likely to live in poverty

read more | digg story

Tuesday, November 20, 2007

Unemployment & Poverty Remain Dramatically High Among Workers w/ Disability

Posted by

DMF

at

5:42 PM

0

comments

![]()

Teaching Diversity to U.S. College Students

"Kim" was Native American, an older non-traditional student, and she was from one of the poorest communities in America: a reservation. She came to my first diversity class with memories of her grandmother's stories. Her grandmother told Kim about when she was taken from her family as a small child, sent to boarding schools run by White Christians, and forced to abandon her language and religion. Kim was a bit afraid of white people.

"Tiffany" was a white woman from a rural town in a Midwest state. Her mother was an activist who through her Lutheran church participated actively during the Civil Rights movement. Her mother had been a high school teacher for years now, and shared stories with her daughter of violence and intimidation in the South. Tiffany felt she was educated on racial issues and she was proud to be a feminist.

"Luke" was a white man from Utah. He was Mormon, and deeply concerned about substance abuse. Though his religion forbid using alcohol, drugs, or even coffee (because of caffeine), he knew a lot of people in his hometown who fell into an addiction trap, including some family members. His experience with religious, ethnic, or racial diversity was highly limited, but he knew a lot about how diverse a group of White Mormons in Utah could be. He knew about those who condemned homosexuality, and he could not help but feel a bit judgmental himself. But, he was an avid reader, and he felt he understood the plight of oppressed people. He felt oppressed himself sometimes because of feeling his religion was under attack.

"Derrick" was a Black man. Don't say African-American, he thought that sounded stuffy. He was Black and proud. He was a religious Christian man, but he had also come out as gay about five years ago. His ex-wife and his teen daughter were accepting. They knew he had been trying to live a lie. His pastor had not been accepting, but he recently found a new church that accepted gay or lesbian members.

* * * * * *

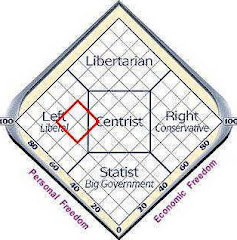

Most students at colleges and universities today are required to take a human diversity course. Given that the United States advertises that it is open, tolerant, and brimming with diversity, educated adults are expected to know how to work with anyone. In the field of social work, the urgency of taking this type of class is obvious. A social work student is a professional in training. Professionals like lawyers, doctors, and social workers, abide by a Code of Ethics, and they are usually self-regulated by a professional organization. Typically, professionals are asked to move past personal biases to serve clients without discrimination, but this is a skill and it needs to be learned.

I taught Human Diversity to graduate social work students in a private elite university. On the first day of teaching this class, I looked out at the 30 diverse faces in my classroom, and asked myself, "What are you supposed to teach them?" Should I teach theories of social psychology or sociology about majority-minority group relations? Should I teach a smattering of facts about various groups? Given the emotional nature of the topic, should I just teach students how to talk about these issues without losing their emotional restraint? Sure, I had planned for class, made an elaborate syllabus, scoured for readings that helped people to develop empathy, but I was fearful of a class meltdown. Many people might think that a classroom of social workers-in-training would be homogeneous-- everyone ready to accept each other with bleeding hearts. Nope!

The truth is that I could arrange to have a class exclusively of white Christian women from the U.S. Midwest, and the diversity in the room would likely still be a source of conflict. The older women resentful of how the younger women take gender equality for granted when they put themselves on the line to fight for what improvements have been made since the 1970s. The Catholic women ready to pounce on abortion as a crime against humanity, while the Unitarians are exploding about someone trying to limit their rights. The liberals arguing with each other about whether pornography exploits or empowers women.

I settled on the basics for understanding other human beings: 1) teach students about critical thinking (how to analyze evidence, recognize assumptions, avoid pitfalls of human logical fallacies, etc.); 2) teach students enough history to provide context; and 3) teach students about relationship skills. All of this would mean reminding students that they would be tested emotionally, because this class was about transcending one's own experience and learning to empathize with the experience of others, even when the implications of "understanding" meant challenging one's own bedrock values.

In this type of heated classroom environment, the tiniest disagreement becomes amplified. One student states that everyone in America should be required to know English, and the bilingual students point out that everyone in America should be required to know more than one language. The best approach for handling the differences of opinion was to require students to go through the steps of critical thinking. As I had learned in high school debate, there is great value in being able to articulate perspectives from multiple sides of an issue.

I knew the goal was to help Kim, Tiffany, Luke, Derrick, and the others learn the tools for understanding each other so they could transfer these skills to their professional work. Kim was filled with fear and anger toward Christians and expressed dismay that Native American religions are widely co-opted or dismissed by majority Americans. Tiffany saw Christianity as a moral code that led to her family's crusade against oppression. Luke could not understand how families faced modern pitfalls without the community of believers he depended upon, and any historical problems with Christianity were in the past as far as he could see. Derrick had found support from his Christian faith to face racism, but he knew only too well that not all people were loved by Christians in the way Jesus demonstrated when he spent time with prostitutes.

To provide the actual lesson of diversity regarding Christianity and other religions, I provided articles and lectures on historical background. We read Jewish, Muslim, or other religious authors recounting the Crusades, the Holocaust, and the dessication of the Native religions through "missionary" schools. Next, I provided the framework for understanding how individuals benefit or become harmed by current infrastructure linked to past wrongdoings. Slavery ended approximately 125 years ago, but White people deliberately broke up slave families, so how long would it take to re-create a functional family unit? Many African-Americans learn from studying their history that not only did Whites split their families to prevent a slave uprising, but only decades after the practice ended, the Whites were already complaining about the weakness of the "Black Family." (see Senator Daniel Monyihan's congressional testimony from the 1950s). Conservative organizations were blaming African Americans for a situation that their ancestors promoted.

Being part of a religious majority in the United States means taking for granted that your holidays will be honored by the government, your communities have lots of choices for places to worship, and commercial outfits decorated with symbols of your faith. This was neither "good" nor "bad" but it was real. In private places, students knew that religion was up to individuals, but what about public places? Could Christians learn to share the public space with people of other minority faiths without feeling that they were "under attack" for seeing a Star of David next to their nativity scene next to the city hall?

In the end, nearly every student reported that he or she DID learn a lot of negative things about the dominant culture in many different categories from religion to gender to socioeconomic status, but they were no less invested in being part of the dominant culture. They had new tools for going out and improving it. By virtue of their increased depth of understanding, they listened to each other, empathized, and realized that maturity, development, and growth required shaking up dusty unexamined belief systems.

If you scan the Internet, you can find all of the degrees of human interactions from open conflict and hostility to empathy and support. Sometimes, the weight of the negativity between individuals/groups is disheartening and leads to pessimism about humans achieving peace in the future. However, after teaching this class, I learned that students can learn to appreciate the faults and strengths of their own groups, and they CAN learn the skills to respect multiple cultures.

Posted by

DMF

at

3:08 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: college students, diversity, multiculturalism, oppression, social work

the Poverty Experts

I was a doctoral student, studying the links between poverty and mental health. I worked at a center where dozens of professors, post-doctorate scholars, and graduate students research poverty and mental illness. Yet, I could not breathe normally within the walls of the poverty research center. After I spent time there, I drove home barely able to keep my foot steady on the accelerator; my foot, as the rest of me, was usually shaking badly. The anxiety was not related to the stresses of graduate school or research. It’s just that I suspect any poor person would feel uncomfortable in the middle class surroundings of the poverty center. Some of the other workers with hidden poverty in their backgrounds have vocalized the same feelings. I found this situation ironic.

The people who work at the poverty center are very professional. There’s nothing wrong with being professional, but such customs as dressing formally are difficult for someone from a low-income background. It was subtle, but I have noticed that my less-than-spiffy clothing draws disdainful glances. I wanted to explain that along with growing up on welfare, I have accumulated school debt and personal debt that dissuade me from buying clothes. Money is tight on a graduate student’s budget, and I also had custody of my younger brother and sister. Most of my coworkers did not know the reasons I cannot afford to wear expensive clothes. I wondered if they have ever considered the source of the differences between us.

Apart from the superficial differences between myself and my coworkers, there are mannerisms and social mores that I tried, often unsuccessfully, to emulate. I lived in fear that my customary style of speech, sense of familiarity with strangers, and my brand of humor will slip through my facade. For example, my younger brother was awaiting sentencing for drug dealing. When my mother and I created his birthday greeting, we enclosed a Monopoly© “Get out of jail free” card. When I shared what I considered to be a clever idea with colleagues, they appeared mortified. It was clear that they did not understand our sarcasm, and they expected the poor to be humorless about their adversities.

When I did show a behavior more common to someone with a disadvantaged background, the tension in the room rises. For instance, there is a norm in scientific research centers to discount personal experience as a source of knowledge. Most of the people I know from my background value the personal account as a means of understanding. So, when someone in a seminar mentioned a “fact” about Head Start that was not true in my own Head Start experience, I voiced my dissenting thoughts. Because my comment was based on my own experience, and not on a statistic I had memorized, there was a moment of silence in the room. The conversation moved on with no further mention.

A poverty research center with an atmosphere that is jarring to a poor person’s sense of safety is a cause for concern. I strongly feel that social workers—in research or in the field—should make every attempt to create safe environments for people with different backgrounds. Furthermore, I question whether the knowledge of poverty my coworkers had gathered through books and journal articles was any more valid than the first-hand knowledge I had gained. Although I was new to feminist theories, it was my understanding that one school of feminist thought has come to value the “ways of knowing” that come from personal experience. I do not ask to dominate the knowledge base concerning economic disadvantage, because I understand that my experience cannot be generalized to others. On the other hand, it is my conviction that my insights could add to the conversation.

I have never been asked to be an expert speaker for a class studying poverty.

The longer I stayed in graduate school, the more convinced I became that I will never be asked to speak on poverty. Was I qualified to give such a talk? I think so. I do not remember a time when my family was not utilizing public income assistance, at least through food stamps. Actually, this isn’t quite true. During my fifth grade year, my family became ineligible for public welfare when aid to two-parent families was cut. As a result, we did not have heat in the house or regular meals. The Department of Social Services took custody of myself and my four younger siblings, because my parents were judged incapable of providing basic needs. Our foster families were paid a subsidy to care for us--financial assistance that far exceeded the monthly allotment once given as welfare to two-parent families.

Recently, speculation ran high in one of my classes on poverty. They were debating what will happen to families following welfare reform; I believed the discussion could be informed by my own life account. Unfortunately, I chose not to share anything personal, because I then understood the disinterest this type of contribution will face. Instead, I did speak up about the statistics I had heard or the theory I had read. This type of comment was accepted with nods of agreement; I guess everyone is on familiar territory when social work academics remain in the world of cold facts.

There are other sketches of poverty I could offer. I have spent a fair share of time in homeless shelters with my family. Some of the correlates of poverty, including divorce, domestic violence, mental illness, or substance abuse, have been regular occurrences in my background. Furthermore, I could speak to the toll of poverty on one’s mental health. I am pleased that data analysts show interest in the statistics about poor people. It is heartening for me to see many social workers go to areas of economic disadvantage to provide services. However, social work researchers and practitioners need to be conscious that a short-term brush with the poor is not equal to understanding their experiences. It is problematic when social workers begin to speak “on behalf” of the poor, without being inclusive of the people themselves.

During my junior year of college, I was interviewed in a focus group of people raised poor. Although some statistics indicate that a childhood spent in poverty is overcome once a person enters college—and thus the middle class—I can tell you there was terror in that focus group. We all recognized lasting effects of worrying about food or shelter. Our sense of self was impacted, because many of the group members mentioned feeling isolated from other college students, and inferior to people in general. Everyone in the group was unable to shop in standard shopping malls; we each felt as though the store help could recognize us as poor people, and thus they would suspect us of stealing. The list of similarities in our anxieties, and our diminished sense of self, was not coincidental. We all knew that poverty had taken its toll on our mental health. As yet, I have not found a single senior researcher interested in collaborating to investigate this phenomenon. Maybe this type of investigation into poverty is based too strongly in daily experience. In the course of day-to-day living, poor people encounter prejudice, discrimination, and pity. This type of experience is emotional in nature, and emotional reactions to poverty are not of interest to researchers. Poverty researchers study observable behaviors of the poor, such as teen pregnancy, joblessness, and criminal activity.

I cannot speak for all poor people, be they currently poor or living with a history of poverty, but I believe we should be given a voice with regard to our life experience. I have been in social work classes where a student dominated the conversation by giving a lengthy description of their personal circumstances; sometimes, these students seemed to be seeking a brief in-class therapy session, or they wanted to show their superior understanding of a topic. There are many ways to use life experience, and like any contribution, there may be abuses. Nonetheless, if research or in-class training included more information about the daily lives of poor people, middle class social workers might feel more comfortable interacting with us in class, in therapy sessions, or at poverty research centers. Poor people like myself could begin to feel less like objects, and more like contributing members of the academic world. How do thoughtful people who have not been poor best relate to those who have had such experience? They could begin by looking at their personal and professional relationships.

Posted by

DMF

at

2:55 PM

0

comments

![]()

Tuesday, November 13, 2007

Poverty Lingers On and On

Today I am celebrating my 32nd birthday. I look 22. I have been asked to produce proof of age for purchasing alcohol as recently as a few months ago. Lucky me. However, I feel 52. No one can tell my background by looking. Not-so-lucky me. Mostly, I bear invisible signs of being broken down. I have had back surgery, heel spurs, arthritis, major depression, anxiety, and endocrine problems. An untreated ear infection during my youth has left me with impaired hearing. Poor nutrition has led to more visible signs of a broken body--bouts with obesity and broken strands of poorly nourished hair. Then there are the prescriptions I need for my peace of mind: an anti-depressant and an anti-anxiety.

1980

My 4th grade class voted in a mock election. I voted for Ronald Reagan. In the real election, my parents voted for him as well. At the time, my father worked full time as a maintenance man, and my mother worked part time as a substitute K-12 teacher. By 1981, my father was laid off from his job. Once his unemployment benefits ran out, we survived on my mother’s work. As the unemployment rate climbed and competition for jobs rose, my mother was called less and less frequently to teach. My parents were not too worried at first. They were confident that the new president would change the economic tide with his trickle down strategies. As time passed, and our economic situation became more ominous, my mother called the welfare office to see if our family could receive assistance. The answer was no. Government policy was that welfare only be given to single parents. In fact, what aid had been available was being cut under Reagan’s economic plan.

Slowly, our family began to curtail spending on things like clothing, heat, water, and finally food. I got my first job in 4th grade. I was nine years old when I became a Des Moines Register newspaper carrier for half of the town of Denver, Iowa. The paper delivery business had been okay in the summer, but as the air grew steadily colder I began what would become my lifelong fear of winter. I’d bundle up in several layers of sweaters, put on heavy boots, and pull on a parka. Each day, I walked about two miles to deliver all of the papers. The exertion from lugging pounds of newspaper taxed my lungs as I struggled to breathe bitterly cold air. The warm, exhaled moisture in my breath made my scarf damp, which in turn, led it to freeze. My mittens never kept my fingers from freezing, and my multiple layers of socks did not save my toes.

When it was extra cold, my eyelashes froze together. Sometimes, I would need to pull my eyelashes apart just to be able to see. Whenever this happened, I became scared. A Des Moines Register paper carrier had recently been kidnapped. I felt safe believing I could fight off any attacker if I could just see him. It was not easy to maintain this bravado being a young girl walking alone in the dark before sunrise. However, I was keenly aware that my contribution to our family’s income was critical.

1981

My younger brother and I got off the school bus at the end of the day on December 18th to find a police officer. He put us in the back seat of his car and told us he was taking us to the hospital without explaining why. During the 12-mile drive, I remember clearly being convinced that my parents and my preschool siblings must have died in an awful car crash. I squeezed my brother’s hand and whispered that I would take care of him. Inside, I was petrified.

Fortunately, I had been wrong. My entire family was alive. They just were not going home together. Child welfare workers were responding to reports that my siblings and I were being “neglected.” When they arrived, the temperature in our house was 38º, except in one room where we all lived around a wood burning stove. The water pipes had frozen at some point. They found our food supply consisted only of canned vegetables taken from our garden that previous summer.

“Mr. and Mrs. Bad Parents, we need to talk to your daughter privately. The officer outside will bring you to the lobby area.”

My parents were not recognizable, because they behaved like obedient children. I was unaccustomed to seeing my parents taking orders. The bearded man told me to take the seat my mother had vacated. He settled across from me with a clipboard. The female police officer sat in a corner of the room.

“Did you eat breakfast today?” he asked quickly.

What a weird question, I thought. I was getting warm in my winter clothes, but my feet were wet and cold. I curled my toes tightly together as I considered his question. But past experience told me that I should answer yes. Grandma and grandpa would also ask this question whenever I went to stay with them. Mama and dad told me to always answer affirmatively.

“Yes, I had cereal, and eggs, and bacon,” I lied.

“Does your family have a refrigerator?”

“It stopped working. We keep things outside to keep them cool.”

“Where do you sleep?”

“I have a mattress in the basement. Why are you asking me these questions?”

“Your parents left your sister and brothers alone at home. They can’t do that. I want you to tell me honestly about how they take care of you.”

I did not like this man with a complete mane of hair around his face. He scared me, and I resented how he talked about my mama and dad.

“Okay, you said you had bacon and eggs this morning. How did your mama cook these for you?”

“We have a hot plate. It’s like a mini stove.”

“Hmm, well, your house does not have any electricity, so how did the food get hot?”

I could only glare in response. At that point, a man wearing a white-coat opened the door. He was obviously a doctor. “I can examine her now,” he told the hairy man.

He held my hands in his, carefully looking at my fingertips for signs of frostbite. He then asked me to remove my boots and socks. I did so unhappily, because I was concerned about my toes never warming up.

1982

I did not like living in the city. Waterloo, Iowa sounds small. It is, but for a rural state, it is the big city. My parents moved there, into government housing and in exchange, the State returned my brothers and sister and me. Eventually, when my parents divorced, the courts calculated my father could afford to pay $75 a month in child support. My father never missed making his child support payments. I delivered my morning newspapers on a new route. It was the city, so it seemed scarier. Now when my eyelashes froze together, I would panic and feel like screaming. Still I told no one of that old fear of being kidnapped. We needed the money.

It was time to go shopping for school clothes. I lowered my head, so my chin touched my chest. Hugging the storefront window as I walked toward the entrance of the second hand clothing store, I allowed my mother to serve as a barrier so that I would not be seen.

“I hate coming here. Someone will see me, and they will tell everyone in school,” I hissed to my mother. “This is going to be my first year in middle school, and I don’t want it to be ruined.”

“Anyone who sees you here must need to shop here as well,” she reasoned.

“But that won’t stop them from driving by and seeing us here.” I slipped into the door, relieved to be off the street. Although I did not want to shop in a secondhand store, the excitement of potentially finding fashionable clothing became the focus of my attention. I left my mother in the shelves dedicated to outfitting young boys, and headed for the girl’s clothing. At the circular racks of clothing, I pulled apart two shirts to allow a full view of an eye-catching red shirt. There was a large stain on the lower right side of this otherwise stylish shirt. In disappointment, I moved onto the next few items. Critiquing each shirt, I passed over most of the selections. There were two shirts and a dress that looked like they would fit in with what my classmates were wearing. In particular, there was a long-sleeved, pastel yellow t-shirt with rainbow colors on the sleeves, like a baseball jersey. This was a rare find, because shirts like these were considered quite popular.

At the changing room, I found that the shirts stretched tightly around my chest. Frustration built as I realized these items did not fit. Revisiting the clothing racks, I spent over an hour looking for other decent clothes. My mom and I left after spending $4 for a skirt and two shirts for me, and a few dollars for my brothers’ clothing.

The next day, I adorned myself with a pale green shirt with small flowers. I put on my new skirt, an ivory fabric with large yellow flowers. I was excited about having new clothes, and I had just gotten new white tennis shoes to top off the outfit. My clothing may not have been name brand, but I felt more confidence from my feminine look. To up the ante, I added sky blue eye shadow and plum blush to my face. It was 1982.

In Mr. Lincoln’s classroom, I spent every afternoon learning social studies and English.

“You look nice today, Deborah” said Mr. Lincoln. I felt a rush of pride. The fact that this nice teacher had noticed my appearance made me feel attractive.

During our lunchtime recess, several girls who were considered popular approached me. For a second, I was exhilarated; obviously, they were coming to include me in their clique, because I had new clothes.

“Where did you get that outfit?” Dawn sneered. “It is so ugly, and it does not match.” She was wearing expensive jeans with a pink polo shirt. Her light blonde hair was feathered back from her face. Like Farrah Fawcett.

Dana chimed in to say, “You need to tell your mom to buy you a bra, because you are totally drooping.”

Finally, another member of the group pointed to my shoes. I don’t remember who she was, because I could not lift my eyes to their faces. She declared, “Those came from a secondhand store.”

“They did not. My mom bought them at JC Penney’s,” I protested.

“You liar. I think my mom donated them last week,” she responded.

Dawn, the undisputed leader of this girl group, concluded their sentiments by saying, “You always smell bad. It sucks that my locker is right next to yours. I doubt you will ever have a boyfriend.”

I didn’t bother to respond, because of the lump in my throat. I spent the rest of the day staring at the ground, not sustaining enough energy to keep my head lifted. On the way home from school, Dawn and her friend Dana followed behind me.

“You’re a loser, and we are going to kick your butt.” Despite my fear, I told them to leave me alone. Another girl was walking down the grass on the other side of the road. She called out, “Is everything all right?” She hastily crossed the street, and stood beside me. I recognized her as the girl who belonged to a strange religion. She was required to wear a dress or a skirt every day, and she could not cut her hair.

Dawn and Dana whispered about both of us, making snide evaluations in audible undertones. Nonetheless, they walked away, leaving me with my savior.

1983

We moved out of government housing. We moved to a new school district. Again. It was 8th grade. We were evicted quickly for inability to pay rent. The night of the eviction, my mother took my siblings and myself to an all night diner. By the morning, the manager, or maybe the waitress, had called the police. They escorted our little weary family to the homeless shelter. The sun was coming up. but I was ready for sleep.

So, we moved again. To the African-American side of town. A few days after moving in, a light-skinned girl approached me as I hung our family’s laundry on the backyard clothesline.

“Hi, my name is Gayle. My next door neighbor Brenda told me you just moved into the neighborhood. Where did you live before?”

Somewhat guardedly, I responded, “I lived in public housing on the West side, over by the high school.” I skipped telling her about the 3-month stay in a rental house. Rather than looking at her, I continued to keep my gaze on the clothespins.

“I know someone who lived over there. Those are nice places…how come you moved to the East side?” Gayle was continuing the conversation, a surprising development. I was unaccustomed to having truthfulness about my background met with acceptance.

“My mom did not like the monthly inspections of our apartment. The managers yelled at her for storing pots and pans in the oven. She wanted to get our own place, before they found a reason to kick us out.”

“Well, are you going to be done with the laundry soon? I want to introduce you to my friend. How come you have to do the clothes washing anyway? By the way, your house has bats.”

Before I went to talk with Gayle and meet her friend, I examined my appearance in the panel of mirrors across our living room wall. A wave of anxiety passed over me as I realized my potential new friend had seen me in red polyester shorts with a see-through blue cotton shirt. My hair had been uncombed, and old eyeliner blackened the area under my eyes. I quickly changed into a denim mini skirt, and a polo shirt. I made sure I put the collar of the shirt up, because I wanted to show that I had fashion sense. Running a comb through my hair, and using tissue to rub away the eye makeup, I felt I looked presentably. Gayle and a heavyset black girl sat on the concrete steps leading to Gayle’s front porch. I took in her glistening Geri curl hair style.

“She has no ass, and she ain’t gonna have much luck getting a man,” the unfamiliar darker skinned girl told Gayle immediately. She made no effort to keep her comment from my ears. Turning directly forward, I swallowed, and blinked away tears. These girls would be no different than the girls who taunted me at the last school. I used my hands to cover my backside, ashamed of my flat bottom.

“But ya know, she got good legs, and big boobs,” she continued. I stopped short, and with shakiness in my words, said, “Why don’t you like me?”

“Aww, girl. I can’t say yet about liking you. I’m just telling’ what I see. I got a few boys in mind for you. A couple of cousins.” We were thirteen years old. A few months later, she went with me to get birth control pills from the free clinic. We were being responsible, but the nurses lectured us. They didn’t understand that we could not risk getting pregnant. It could make us stay poor.

1985

Gayle went away for the summer last year and left me to work. Not this year, though. I was going to go with her to Luther College for the summer, taking classes, meeting other kids like me, and maybe making friends. I was accepted to Upward Bound, a government program that assists low-income high school students with attending college by providing college prep experiences. This program was going to save my life. I met friends, began to crack the armor surrounding me. Old notes I read from my file say, “She is really coming out of her shell.”

The Upward Bound summer was supposed to last for six weeks. My family desperately needed money, and the middle weeks of July offered the promise of jobs working in the cornfields. For two to three weeks each summer, people earn minimum wage helping to create hybrid corn. With the opportunity to earn money, I left Upward Bound for two weeks, regretting intensely my need to leave. With my field work money, I bought my family its first car in four years—a 10-year old bright yellow, but very rusty, station wagon. It was an investment that would allow for more employment.

Posted by

DMF

at

4:06 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: first-person, memoir, poverty

the Souls of Christians

Growing up Lutheran, my mother went to New Guinea on a Lutheran mission in the late 1960s. When she returned, her family, including her domineering father, had converted to the LDS church (Mormons). She dutifully followed suit, and traveled to Salt Lake City, Utah to absorb her new religion. When church elders told her that God had informed them she belonged with my father, she married him. The drumbeat message to be a good mother consumed her, and she had six children as part of her understanding of what Church leaders expected of a good Christian woman. She called feminists, "libbers," condemned abortion, and embraced traditional roles for women: wife and mother.

When my parents met seemingly even more devout Mormons, specifically fundamentalists, they were enamored. A time-limited (Thank God) saga involving polygamy ensued. After realizing that she had been led astray by false prophets, my mom went on a quest to find God's church. There was a period where both of my parents held home "Sunday School" with us: teaching Bible stories, drawing Biblical events, and learning right and wrong. Then, there were months, sometimes years of membership in churches such as the Vineyard, Seventh Day Adventists, Christian Scientists, Methodists, Baptist, a brief Jewish exploration, and several others I can no longer remember clearly.

My tremendous, yet vulnerable mother is truly one of God's children. Unfortunately, her reluctance to question those "authorities" who claim to speak for God, left her prey to the worst kinds of fanatics. She became overly obedient, failing to exercise independent thought or judgment. When indoctrination becomes severe enough, even the conscience can be usurped. Her own struggles to make it right with God mirror what a great many American Christians are presently doing. They are following fanatic leaders who lead them astray from what Christianity really means. The following website contains several examples of people who are clearly raising themselves above others and acting contrary to the teachings of Jesus:

http://www.reandev.com/taliban/

For all of my mother's problems with organized religion, including the times when she put aside her judgment, she has maintained a personal spiritual integrity that I realize shaped my own beliefs about right and wrong. One lesson is particularly salient. Refusing to reject anyone, she befriended a male-to-female transsexual person when I was in high school. They met at the Salvation Army where our family ate lunch every weekday but Wednesday when the soup kitchen was closed. In our small Iowa community, people with differences stand out, and this person had a number of barriers to gender resolution. She clearly felt like a woman, but she was poor and could not afford surgery. Thus, she grew her hair, wore a padded bra, and wore women's clothing. Without hormone therapy, she had a visible five-o'clock shadow, and her body was stocky even by male standards. Her situation led to ridicule throughout the community.

When mom requested that this person pick me up from school, I was humiliated. I tried to slink into her car without being seen by peers. It didn't work, and several days of I already dealt with the stigma of being poor, and there was several bullies at the school who had targeted me for years. They would taunt me about my clothing, my outdated hairstyle, my cleanliness and associated "alleged" smell, etc. Once I had a chance to confront my mother, I asked her why she tortured me by sending this person to pick me up from school.

She told me that a good Christian looked into the souls of others and offered them Christlike love if they were good people suffering with adversity. It was not her place to judge, to criticize, or to demean. She told me that I should be ashamed of myself for letting the cruel, childish opinions of others influence my own treatment of others. She was right. Pure and simple.

http://www.sojo.net

Posted by

DMF

at

3:42 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: christianity, kindness, love, religion

Saturday, November 10, 2007

11 Year Old Girl Kills Herself Because of Poverty

A girl aged 11 hanged herself in a Philippines shanty after leaving a letter and diary depicting a life in rampant poverty, newspapers here reported Thursday.The case put a human face to poverty blighting the nation, where nearly 14 percent of the 87 million population live on less than a dollar a day.

read more | digg story

Posted by

DMF

at

11:30 AM

0

comments

![]()