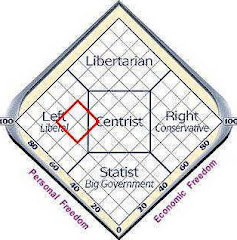

Our first Christmas vacation morning was ruined by this alleged business. As it turns out, this dealership is not about Toyota, it is a center for right-wing propoganda.

Our first Christmas vacation morning was ruined by this alleged business. As it turns out, this dealership is not about Toyota, it is a center for right-wing propoganda.

This is a website paying homage to wisdom. Education and experience combined with the power of critical thinking have served me well, and I hope others will be encouraged to consider their own life's learning.

Our first Christmas vacation morning was ruined by this alleged business. As it turns out, this dealership is not about Toyota, it is a center for right-wing propoganda.

Our first Christmas vacation morning was ruined by this alleged business. As it turns out, this dealership is not about Toyota, it is a center for right-wing propoganda.

Posted by

DMF

at

1:42 PM

10

comments

![]()

Understanding and Experiencing White Privilege:

Even after nearly 8 years in a graduate social-work program—in an environment in which discussion of oppression and privilege occurred frequently—I still had trouble with the idea that I had personally benefited from many advantages. It was not that I cognitively denied my privileges, particularly those gleaned from being White; my challenge was the intersection of being White and growing up poor. I struggled with feeling privileged when I could not get over feeling deprived; I could make a direct connection between current miseries and lifelong disadvantages. Educating others around me who just "didn't get economic or class oppression" drew my focus away from my own white privilege.

Roots of an Identity

Although I am a white, heterosexual woman, the identity most salient throughout my life was "poor trash"—a welfare child. Many life experiences reinforce the importance of this identity over the more privileged identities I enjoy. Both of my parents suffered from psychiatric illnesses. My mother received disability payments, and my father was employed as a janitor which meant minimal income. Economic struggles within my family led to bouts with homelessness, daily reliance on the Salvation Army for meals, and dependence on charity from public and private sources. Lack of food and heat led child-protective services to remove my siblings and me from my parents to be placed in foster care. When we were eventually returned to our parents the strain of family separation and poverty led my parents to divorce shortly thereafter. My mother became a single parent to six children, while my father moved into a roach-infested single room occupancy hotel.

The neighborhood in which we were being raised was dangerous and dilapidated. Indeed, the rampant negative influences likely contributed significantly to the fact that three of my younger siblings were mandated to services within the juvenile justice system, and two of them became drug dependent. Eventually, one of my brothers committed suicide. I will always be convinced that poverty and our childhood life circumstances played the largest role in his death.

My departure from this life of poverty at the age of 17 was the result of support from family and friends, an extensive series of governmental interventions (ranging from Head Start to Project Upward Bound), and a natural inclination toward academia. As I was driven off to college, I felt relieved to have escaped that life of dispossession. But unfortunately the feeling was short-lived, for it was during college and graduate school that I discovered the seemingly permanent effects of my economic history. The majority of my classmates came from middle-class to upper-middle-class families. There were daily reminders of our differences.

In political science and economics classes, my privileged college classmates degraded welfare recipients. I was too frightened of social exclusion to speak up. Instead, I silently sat in isolation, absorbing the significant social distance between us. Outside of class, many acquaintances were frustrated with my seeming "unwillingness" to spend more time with them in social activities and less time at work. They did not understand that for me, work was not a choice.

My full-time work schedule throughout college did not allow much time for socializing. Whether I was serving other students food at the school's cafeteria during the day or taking their orders at the popular local restaurant in the evening, I would overhear college classmates complaining about reductions in their allowances from $500 a month to $250. They did not have to pay their college expenses, and they even got an allowance. They did not need to work. I fantasized about what that would be like. It was hard not to feel bitter as my own class work often got behind in a heavy work week. Chronic fatigue also made me prone to headaches, stomach pain, and colds.

As it turned out, being poor had shaped my identity, had somewhat become my identity, and continued to play itself out. During graduate school, I found myself in the role of parent when I obtained custody of my two youngest siblings, accumulating over $125, 000 in student loan debt while attempting to raise them on a graduate student's stipend and other meager employment. It was under these circumstances of economic hardship that I studied oppression and privilege in my graduate classes and learned extensively about white privilege. Certainly, it felt to me as though my entire life had been defined by deprivation. If there were white privileges to be recognized, I could not see them. In my mind, what on earth good had it done to be white? It had not spared me hunger, frostbite, lice, poor medical care, ridicule, violence, or trauma. This feeling of deprivation was especially true here because other graduate students, including students of color, who had spent their lives in material comfort, were by far the majority in graduate school.

The Embers of Transformation

Eventually, I gained an intellectual, if not intuitive, understanding of privilege through my graduate program. Vowing to continue work on my own issues of privilege, I decided to become a co-facilitator with a well-regarded lead instructor, Dr. Michael Spencer . Dr. Spencer offers multicultural dialogue groups as a major means for learning about social justice, oppression, and privilege in his Contemporary Cultures in the United States class. I maintained the goal of focusing on my privileged identities, but I often felt ambivalent. On the one hand, I felt bitterness, guilt, and defensiveness at being blamed for my culpability in race oppression as class members of color described their experiences. On the other hand, I felt envy and bitterness toward those individuals who had been economically privileged throughout their lives. I craved their basic privilege of getting fundamental needs met and the sense of security that elicited.

About mid-semester, I was asked by Dr. Spencer to give a presentation on classism and poverty. He knew this was an area I knew a lot about. As I presented general information to the class, I shared specific details from my personal experiences to give fellow students a sense of how economic labeling and stigmatization make an impact. At one point, I showed the class a Child Protective Services document that declared me guilty of child neglect when I left two of my siblings in the house while I went to rescue another younger sibling being beaten by kids at the local park. I was 12 years old at the time. We discussed whether the guilty verdict would have occurred for a middle-class family under the same circumstances, and most class members agreed that it likely would not have.

The presentation stirred a mix of emotions in me. To share the lack of power, the deprivation, and the humiliation was empowering. Nonetheless, the stigma of poverty and child neglect, even though I was only 12 years old at the time, still stung. I felt I had performed a duty to other poor people by telling our story, but the cost was shame that took weeks to shake off.

At the end of the presentation, an African-American graduate student I respected a great deal approached me. She told me honestly, "I feel bad for you; but to be blunt, by the end of your talk, I was still thinking, 'So what? You're still White.' I guess I think that being White makes a big difference." Her words stung; her expression seemed defiant and accusatory. It felt as though my oppression was deniable, because I was white. The weight of race oppression was her burden. To me, it felt as if she could not see my burden of class oppression or her own class privilege as long as her awareness stayed entirely within race oppression.

It dawned on me, eventually, that I was not going to be able to own my white privilege until I let go of enough of my own oppression to really listen and internalize the privilege. My classmate's comment was a precipitant to the gradual coherence and redirection of my conflicting thoughts and feelings. There we had been, both in pain from dealing with the ramifications of oppression, yet we had been at odds.

When I recollected that exchange later on, the importance of accepting my white privilege became clear to me on an emotional level because, if I was unwilling to move beyond my oppression, how could I expect anyone else to do as much? This meant I was going to have to really attend to all of the daily instances in which my race advantaged me. If I applied for an apartment, I knew any rejection would be because I didn't have enough credit. I did not have to question whether my race was a factor. I had personally witnessed millions of examples of white privilege as I grew up in a predominantly African-American neighborhood; but I had not focused on these. As I became more willing to explore the totality of my life circumstances, I became more conscious of my "privileged identity" and not just my "oppressed identity."

During this period of awakening and transformation, I was fortunate to have the guidance of authors such as June Jordan (2001), who taught me that oppressed people have to examine their privileges just as often as they grapple with their oppression. Jordan (2001), an African-American woman, described an interaction with a White, female student who declared her (Jordan) to be "lucky" for having lived with oppression. From the student's perspective, dealing with oppression gave Jordan a cause or purpose to her life. Alternatively, this student felt she was "just a housewife and mother," and thus, a "nobody" (p.39). Jordan used this experience to reflect on the ramifications of gender, race, and class oppression. In that exchange, she saw that this student did not see others' oppression as her own cause or her purpose. There was no unity between them as they struggled against gender and race oppression.

Later in her essay, Jordan (2001) writes about an African woman and an Irish woman joining in solidarity to solve a problem, "It was not who they both were but what they both know and what they were both preparing to do about what they know that was going to make them both free at last" (p.44). This was the lesson. I knew my own oppression, but without understanding my white privilege—privilege being the constant companion to oppression— I could not "know" or work against race oppression. If I didn't fully know what others with whom I wanted solidarity experienced, we would be unable to be free of our respective oppressions together.

The Repeating Process of Self-Examination: Conclusions and Lessons Learned

Examining one's own privileged status is a constant process. I have had to continually revisit my tasks as a member of oppressing groups. Freire (1970) called this repeated process of self-examination, "critical consciousness." Specifically, I have to repeatedly remind myself that I cannot expect others to examine their economic privileges if I am not willing to work on owning my white privilege. I knew the vexation that came from waiting for others to accept their class privilege; that economically secure people took for granted their safe neighborhoods, regular meals, and designer clothes always seemed to make poverty worse.

So I planned to appreciate my white privilege, notice it, and then work to extend these privileges to others. For example, not long ago, I was riding on a city train. A beautiful African-American child, about 4 years old, was smiling and talking to passengers. When this little girl and her mother exited the train, a white man with all of the markers of being from a lower-class background made a derogatory comment about the young girl's hair, which had been combed out to a full Afro. I winced to hear his insensitive and disparaging views. He was part of the system of white oppression, a blatant racist asserting cultural dominance based on skin privilege. Only a few moments later, an aging African-American male trudged up the aisle of the train carrying a mop and a bucket. He looked weary, confined to cleaning up the mess made by other people on train cars.

This story is relevant in my transformation because my previous instincts would have been to overlook the obvious signs of race oppression. In the past, I would have mentally felt united with the poverty of the janitor, feeling connected to him by the fact that I had scrubbed my share of toilets, and because my father has been a janitor most of his life. I would not have focused on what I had in common with the lower class white person, or how I personally benefited from systemic oppression based on race. However, this time, I understood in that moment the privilege of being White, and I reminded myself how my race had almost certainly played a beneficial role in my escape from poverty. How many people had just assumed, in part because I am white, that I was bright and easily educated? How often had my "merits" been recognized where they may have otherwise been overlooked if I had darker skin? In that moment, I recognized that I was exceptionally blessed to be riding to a sports event on the train, enjoying my free time, having the funds to pay for leisure, and possessing the capabilities to avoid doing the kind of work that would put that immutable wearied look on my face.

More and more, I recognize that I am fortunate to have had experiences with being disadvantaged. The circumstances of my life have allowed me to develop an empathy that has resulted in deeper interpersonal relationships with others. The weight of oppression has alerted me to the need to participate actively in efforts to change societal injustices. I have come to consider much of what is white privilege as a set of basic rights all people should be entitled to. I am working, through social and political action, dialogue in the classes I teach, and constant reexamination of my self-awareness, to challenge the oppression-privilege dichotomy. There is a certain gift in feeling as if, just maybe, I might be "a part of the solution."

References

Goodman, D. (1995). Difficult dialogues: Enhancing discussions about diversity. College Teaching. 43(2), 47-52.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Jordan, J. (2001). Report from the Bahamas. In M. Andersen & P. Hill Collins (Eds.). Race, class, and gender: An anthology. (4th ed.) (pp. 35-44). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

McIntosh, P. (2001). White privilege and male privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondences through work in women's studies (1988). In M. Andersen & P. Hill Collins (Eds.). Race, class, and gender: An anthology. (4th ed.) (pp. 95-105). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Miner, B. (2001). Taking multicultural, antiracist education seriously: An interview with Enid Lee. In M. Andersen & P. Hill Collins (Eds.). Race, class, and gender: An anthology. (4th ed.) (pp. 556-562). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing.

Reed, B., Newman, P., Suarez, Z., & Lewis, E. (1997). Interpersonal practice beyond diversity and toward social justice: The importance of critical consciousness. In C. Garvin & B. Seabury, (Eds.). Interpersonal practice in social work: Promoting competence and social justice (2nd ed.) (pp. 44-77). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Wade, J.C. (1993). Institutional racism: An analysis of the mental health system. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 63(4), 536-44.

Posted by

DMF

at

6:19 PM

0

comments

![]()